Ideological division was tearing the nation aside. Factions denounced one another as unpatriotic and evil. There have been tried kidnappings and assassinations of political figures. Public monuments and artwork have been desecrated everywhere in the nation.

This was France in the midst of the sixteenth century. The divisions have been rooted in faith.

The Protestant minority denounced Catholics as “superstitious idolaters,” whereas the Catholics condemned Protestants as “seditious heretics.” In 1560, Protestant conspirators tried to kidnap the young King Francis II, hoping to switch his zealous Catholic regents with ones extra sympathetic to the Protestant trigger.

Two years later, the nation collapsed into civil struggle. The French Wars of Religion had begun – and would convulse the nation for the following 36 years.

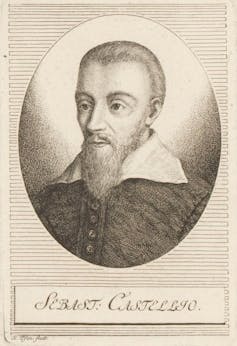

I’m a historian of the Reformation who writes concerning the opponents of John Calvin, a main Protestant theologian who influenced Reformed Christians, Presbyterians, Puritans and different denominations for centuries. One of probably the most important of Calvin’s rivals was the humanist Sebastian Castellio, whom he had labored with in Geneva earlier than a bitter falling out over theology.

Soon after the primary struggle in France broke out, Castellio penned a treatise that was far ahead of its time. Rather than be a part of within the bitter denunciations raging between Protestants and Catholics, Castellio condemned intolerance itself.

He recognized the primary downside as either side’ efforts to “force consciences” – to compel folks to imagine issues they didn’t imagine. In my view, that advice from practically 5 centuries in the past has a lot to say to the world today.

Foreseeing the carnage

Castellio rose to prominence in 1554 when he condemned the execution of Michael Servetus, a medical doctor and theologian convicted of heresy. Servetus had rejected the usual Christian perception within the Trinity, which holds that the Father, Son and Holy Spirit are three individuals in one God.

Iantomferry/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Already condemned by the Catholic Inquisition in France, Servetus was passing by Geneva when Calvin urged his arrest and advocated for his execution. Servetus was burned alive on the stake.

Castellio condemned the execution in a outstanding guide titled “Concerning Heretics: Whether They are to be Persecuted and How They are to be Treated.” In it, Castellio questioned the very notion of heresy: “After a careful investigation into the meaning of the term heretic, I can discover no more than this, that we regard those as heretics with whom we disagree.”

In the method, he laid the mental foundations for religious toleration that may come to dominate Western political philosophy through the Enlightenment.

But it took centuries for non secular toleration to take maintain.

In the meantime, Europe turned embroiled in a sequence of non secular wars. Most have been civil wars between Protestants and Catholics, together with the French Wars of Religion, a sequence of conflicts from 1562 to 1598. These included one of probably the most horrific occasions of the sixteenth century: the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of 1572, when 1000’s of Protestants have been slain in a nationwide massacre.

Castellio had seen the carnage coming: “So much blood will flow,” he had warned in a treatise 10 years earlier, “that its loss will be irremediable.”

Cantonal Museum of Fine Arts/Wikimedia Commons

Remembering the Golden Rule

Castellio’s 1562 guide, “Advice to a Desolate France,” was a rarity within the sixteenth century, for it sought compromise and the center floor fairly than the non secular extremes.

With an awfully trendy sensibility, he determined to make use of the phrases either side most well-liked for themselves, fairly than the unfavorable epithets utilized by their opponents.

“I shall call them what they call themselves,” he defined, “in order not to offend them.” Hence, he used “Catholics” fairly than “Papists” and “evangelicals” rather than “Huguenots.”

Castellio pulled no punches. To the Catholics, referring to many years of Protestant persecution in France, he stated: “Recall how you have treated the evangelicals. You have pursued and imprisoned them … and then you have roasted them alive at a slow fire to prolong their torture. And for what crime? Because they did not believe in the pope, the Mass, and purgatory. … Is that a good and just cause for burning men alive?”

To the Protestants, he complained, “You are forcing them against their consciences to attend your sermons, and what is worse, you are forcing some to take up arms against their own brothers.” He famous that they have been utilizing three “remedies” for therapeutic the church, “namely bloodshed, the forcing of consciences, and the condemning and regarding as unfaithful of those who are not entirely in agreement with your doctrine.”

Sepia Times/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

In quick, Castellio accused either side of ignoring the Golden Rule: “Do not do unto others what you would not want them to do unto you,” he wrote. “This is a rule so true, so just, so natural, and so written by the finger of God in the hearts of all,” he asserted, that none can deny it.

Both sides have been making an attempt to advertise their imaginative and prescient of true faith, Castellio stated, however each have been going about it the incorrect method. In specific, he warned in opposition to making an attempt to justify evil conduct by interesting to its potential results: “One should not do wrong in order that good may result from it.”

In another essay, he made the identical level to argue against torture, writing that “Evil must not be done in order to pursue the good.” Castellio was the anti-Machiavelli; for him, the ends didn’t justify the means.

Force doesn’t work

Finally, “Advice to a Desolate France” argued that forcing people to your own way of thinking never works: “We manifestly see that those who are forced to accept the Christian religion, whether they are a people or individuals, never make good Christians.”

Americans, I imagine, would do nicely to bear Castellio’s phrases in thoughts today. The nation’s two dominant political events have become increasingly polarized. Students are reluctant to speak out on controversial matters for worry of “saying the wrong thing.” Americans more and more assume in binary terms of fine and evil, pals and enemies.

In the sixteenth century, Christians did not heed Castellio’s advice and continued to kill one another over variations of perception for one other hundred years. It can be sensible to use his concepts to today’s bitter divisions.