Edinburgh, Scotland

—

As “Auld Lang Syne” takes its annual spin round the globe on New Year’s Eve, its refrain belted out by revelers younger and previous, Edinburgh’s Poet Laureate Michael Pedersen says the music’s enduring energy lies not in custom alone, however in its uncanny skill to bind folks collectively.

Pedersen, a prize-winning Scottish poet and creator who’s the present Writer in Residence at the University of Edinburgh and the metropolis’s Makar, or Poet Laureate, advised NCS that the music’s customary rendition at midnight on December 31 was by no means formally ordained — it merely felt proper.

“For generations, it’s been sung at New Year because it’s perfect for it,” he mentioned. “There’s nothing in the song that dictates it should be sung then. People just had an emotional compass for it. They gathered outside town halls and sang it, and it drifted — like a great, beautiful glacier of song — into that New Year position.”

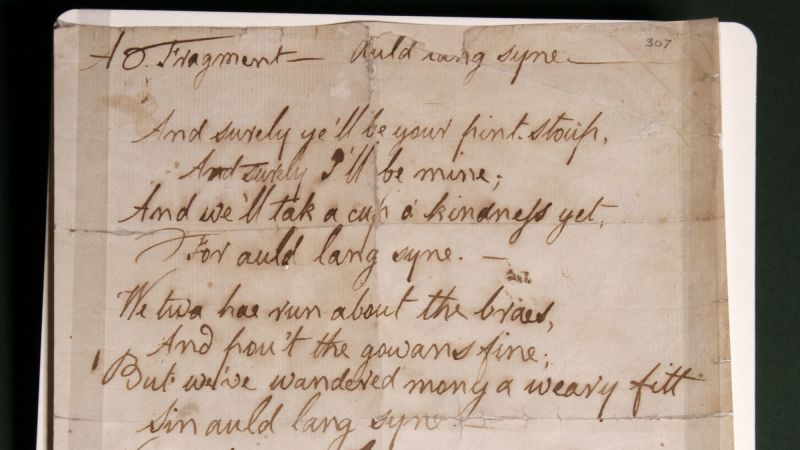

Despite its recognition, few would declare to know all the phrases to the music, first written down by Robert Burns in 1788 – however that has finished little to dent its enchantment.

The phrase “auld lang syne” interprets loosely to “old, long since,” although Pedersen says a contemporary equal could be “for old times’ sake.” At its coronary heart, he mentioned, the music is “a tale that looks back at childhood friendship, rekindled with a handshake and a goodwill drink.”

“It’s a song of reunion, not parting,” he added. “It’s about celebrating happy days gone by and the glorious bonfire in the belly when you come back together.”

As a Scotsman, watching the music circle the planet every year appears like “sending out the Scottish bat signal,” Pedersen mentioned.

“Auld Lang Syne is very much born in Scotland, though it’s become the ultimate international citizen,” he mentioned. “Everyone has made it their own. What a beautiful expression of art and humanity — to write something national and deeply personal, and have people project their own lives into it.”

Part of its endurance, he argues, is bodily. The music isn’t simply sung — it’s carried out.

“It happens at such beautiful moments: the end of the year, weddings, big gatherings,” he mentioned. “You join hands, you form a circle, you create a physical expression of friendship. Most people hum through the verses and come in strong on the chorus, and it pulls us all together. It’s a mellifluous, song-sized hug that’s survived the centuries.”

As for the choreography, Pedersen says the arm‑crossing second comes later than many suppose.

“Traditionally, you hold hands for the first five verses,” he mentioned. “Then on the fifth, everyone crosses their arms, still holding their neighbors’ hands, and runs in and out of the circle. Of course, culprits and rogues will run in at various points — that’s part of the beauty, the calamity of it.”

The query of authorship stays one among Scottish literature’s most enduring debates. Robert Burns claimed he merely wrote down a model he heard in a training inn, later adapting it to suit a tune.

“We have no evidence of how much he adapted,” Pedersen mentioned. “It could have been a word or two, or a massive Burns rewrite.”

Burns’ writer, George Thomson, altered the music once more after the poet’s dying, producing the melody recognized at present.

“Even now, critics argue over whether Burns was leading us astray, and it was his all along,” Pedersen mentioned.

“He was known to avoid attributing some of his own work — sometimes because it was too heretical, sometimes because he wanted to see how people reacted without his fame behind it. It remains a beautiful, mellifluous mystery.”

Pedersen has now added his personal contribution to Scotland’s New Year canon with “Boys Holding Hands,” a poem impressed by Burns and written, he mentioned, from a lifelong devotion to friendship.

“I’ve always worshipped at the altar of friendship,” he mentioned. “I wanted to write my own poem about joining hands in celebration of friendship, inspired by Burns. ‘Boys Holding Hands’ is that piece — taking your pal’s hands in celebration of all the times you’ve had and all the times you’re going to have.”

The poem, he mentioned, can be a delicate problem to the emotional constraints positioned on males.

“There’s a real bravado to masculinity that causes us to trap a lot of our emotions in our belly and dissolve them like a piece of gristle until they’re voiceless,” he mentioned. “We have to let all that soppy, sumptuous sentimentality spill out to make ourselves better, more equipped, more loving human beings.”