EDITOR’S NOTE: The NCS Original Series “American Prince: JFK Jr.” airs at 9 p.m, ET/PT on Saturday nights.

John F. Kennedy Jr. launched his journal “George” 30 years in the past, when it felt like publications in New York City have been essentially the most highly effective and glamorous factor possible. Gossiped-about editors prowled town in black automobiles and flew above the world on the Concorde, gleefully busting their huge budgets as they canceled and created careers.

And then there was John. He preferred to journey his bike round city.

“They called him a himbo. The New York Post used to tease him all the time,” mentioned longtime journal author Nancy Jo Sales, who lined Kennedy for People journal. She remembers him as being variety, dog-loving and all the time gracious. “He was no dummy. I mean, look who his parents were. His mother was one of the most cultured people like ever in American social history. His father was — hello? He was a very smart guy. And I think what he really, really loved was journalism. He wanted to make a great magazine. And why would a guy like John Kennedy make a magazine like George? Because that was the coolest thing to do at that time — be in magazines. It was the most exciting thing to do, and it was the thing that mattered.”

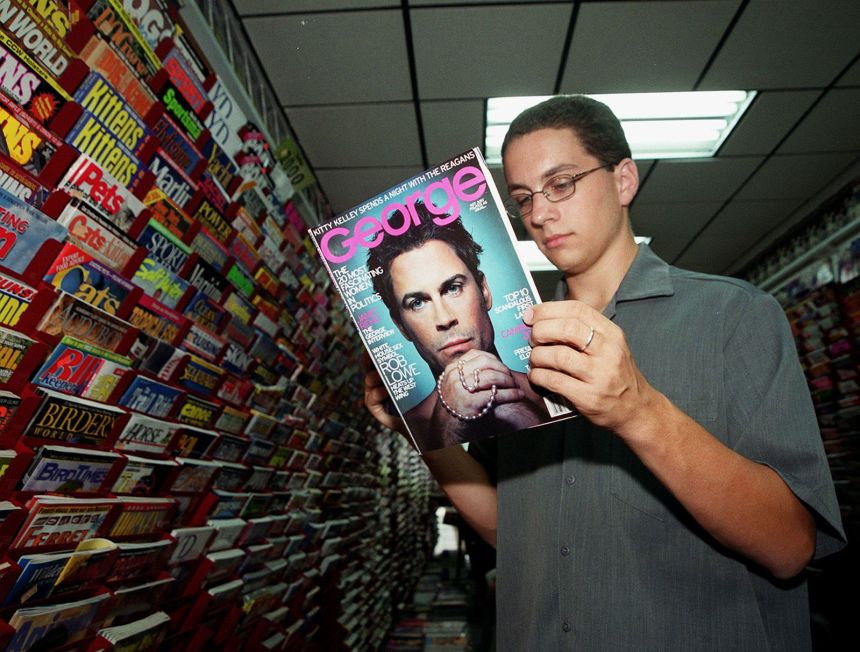

After years of scheming, George arrived in September 1995. It was meant to merge politics and celeb in a manner that felt new — full with Cindy Crawford in George Washington costume on the debut cowl. “Magazines still were fat and rich enough to be ambitious,” mentioned the author Sasha Issenberg, who was a teenage intern at George. “John came to this with a big animating idea, not only about what the magazine could look like, but about a bigger shift that was underway in American politics and culture.”

This was, in any case, 1995: the 12 months Selena was killed, the 12 months the federal constructing was bombed in Oklahoma City. O.J. Simpson was discovered not responsible of killing his former spouse, and a doomsday cult killed 14 individuals in a sarin fuel assault within the Tokyo subway. All the political components of our present chaotic second have been already seen for individuals who knew to look.

And so, a Kennedy joined the ranks of the leaders of Vogue, People and Time, beginning George with the corporate Hachette Filipacchi, dwelling of Elle and Woman’s Day.

“If you wished to know what was cool within the ‘90s, you looked at a magazine. Now you probably look at social media. But back then, editors at magazines were the ultimate tastemakers,” said Amy Odell, fashion journalist and author of the 2022’s “Anna: The Biography.”

When George was conceived, Anna Wintour was starting to turn into extra well-known than the supermodels she placed on her covers. The movie “The Devil Wears Prada” — which turns 20 subsequent 12 months, if you wish to really feel outdated — cemented her standing as character and caricature. But she wasn’t alone. There was Graydon Carter, the Canadian rail employee who turned editor of Vanity Fair, and Tina Brown who got here from London and have become well-known as an editor as a result of nobody might inform if she was simply sensible or simply outrageous — and Jane Pratt, whose Sassy journal was so influential that her subsequent journal needed to be named simply Jane.

Unlike George, which was not named John.

“He was a famous person looking for a niche to slot himself into as a famous person,” mentioned Matt Haber, longtime print and digital editor, and editor of Gazetteer SF. “George was meant to be that. If he was around today, it would be a multimedia company, right? He would have a podcast anchoring it, and there’d be a show on Netflix, like ‘JFK Presents.’ He would be like, ‘Call Her Daddy’ or Joe Rogan, like he’d have a whole constellation of content around him. But back then, magazines were still the center of the culture — and if you wanted to make a statement, that’s the way you did it.”

The years of extra and flower deliveries

What did a journal even do? For one, magazines fed Hollywood — much more than you would possibly suppose. An enormous enterprise funneled content material from magazines, creating films from articles: “Boogie Nights,” “Hustlers,” even “Shattered Glass,” from a journal article about a journal scandal. The Fast and the Furious and Top Gun franchises have been primarily based on journal articles. Magazines invented and distributed the photograph shoot, created literary stars like Ta-Nehisi Coates, Malcolm Gladwell and David Foster Wallace. They fed tv — within the Nineties, Time built a TV studio within the workplace so their reporters might extra simply go on NCS.

Their franchises turned common references: the September subject, the Swimsuit Issue, the particular person of the 12 months, the Playboy centerfold, the New Yorker cartoon. They modified individuals too, for good and for worse. The rash of lad mags, crowded with bikini babes and unhealthy recommendation for dudes, actively influenced the lads to be extra sexist; research confirmed that publicity to vogue magazines within the Nineties appeared to make girls hate themselves.

This all made fairly a bit of cash.

“I was an intern at Entertainment Weekly in 1998 and we got paid a salary,” mentioned Haber. “We got paid overtime if we stayed past six o’clock. We got a dinner voucher if we stayed past like 6:30” — plus automobile service dwelling.

“On Thursday and Friday nights, they’d have a bar,” mentioned Kurt Andersen, co-founder of Spy and former editor of New York journal, about his years as an structure and design critic at Time. “They served dinner, if you wanted their sh*tty dinners there. It was old school, in a way that now seems, like, 19th century to me.”

“I would say, ‘Oh, I want to go write about the World’s Fair in Seville, Spain. ’ ‘Okay, sure. Go.’ I was never, ever turned down.”

The executives and stars loved an excellent higher class of perks. For the very high editors, Condé Nast secured mortgages for editors and high staffers or gave them money to purchase Manhattan flats and townhouses. Some of their contracts had a wardrobe allowance, simply $40,000 a 12 months, plus weekly flower deliveries and every day drivers. Writers like Dominick Dunne might earn half a million {dollars} a 12 months whereas staying without charge in an countless array of pricey lodges.

“The excess was legendary. For years, there simply were no budgets,” wrote Michael Grynbaum in “Empire of the Elite,” his current historical past of Condé Nast. In 1989, he wrote, Tina Brown, because the editor of Vanity Fair, flew the photographer Annie Leibovitz 41,000 miles in top quality to {photograph} topics for a portfolio. The author Ann Patchett, uninterested in having houseguests, as soon as pitched a story to Gourmet about staying alone in an costly lodge for a week simply so she might get a break. (The Hotel Bel-Air was apparently beautiful.)

For Lisa DePaulo’s first story at Vanity Fair, she mentioned, “I had to interview someone in Delray Beach, and I said, ‘There’s a great Marriott right near here, and it’d be a great place for me to stay.’ And the travel department was like, ‘You’re with Vanity Fair. You can’t stay at the Marriott.’”

People journal “was, at the time, the most profitable magazine in America, and there was nothing that seemed off limits or extravagant,” mentioned Janice Min, longtime journal editor and current honcho of The Ankler. “When I worked at InStyle, the whole staff went on an off-site to Antigua.” Fortune journal once spent $5 million taking its workers to Hawaii.

George was not fairly located on the middle of imperial luxurious. “At Condé Nast, you had Vogue and Vanity Fair and The New Yorker in the offices next to you. At George, we had Road & Track and Car Stereo Review,” mentioned Issenberg. But there have been upsides to having a Kennedy as a boss, past his appears and good mood, clearly. He took the whole workers to a Yankees playoff sport, his buddy and George editor Gary Ginsberg mentioned. Kennedy all the time had nice entrance row seats to the Knicks, and distributed the piles of designer garments and ties that have been despatched to the workplace.

The workplace did have a distinct taste of Kennedy mayhem. “It was a constant circus of people coming in and out. You never know who you’d run into on any given day: Demi Moore, Barbara Walters, Katie Couric,” mentioned Ginsberg.

And his very existence introduced the publication an important commodity a journal might have: buzz. Though it got here with baggage. “For true American royalty, you had JFK Jr., and the Kennedys at the time, and so it never felt like it was going to necessarily land or hit, because it had that sort of sheen of a vanity project,” mentioned Min. “It obviously got a really disproportionate amount of coverage, probably with a strong hint of schadenfreude from other media that didn’t necessarily love the idea. Even though they might have loved him, they didn’t love the idea of, basically, an OG nepo baby coming in to try to stake a claim in the industry.”

Despite these doubts, George got here in scorching — for staffers within the first 12 months, it was a wrestle to write down and edit sufficient tales to fill all the mandatory pages, as a result of the journal saved rising because the advert gross sales staff saved promoting.

“It just seemed like if you had a good idea for a magazine, you could touch gold, with advertisers and with readers,” mentioned Elinore Carmody, the founding writer of George.

The ambition was sky-high, if generally wobbly. The journal paid Gore Vidal “like $25,000 or whatever” for a story about George Washington within the first subject, former George editor Hugo Lindgren told the Hollywood Reporter. Vidal delivered a piece about how horrible George Washington was — and Kennedy selected to not publish it.

In the leadup to the 1996 nationwide political conventions, the magazine secured Norman Mailer, the legendary chronicler of the chaotic 1968 Democratic National Convention, to cowl them. The author named his value and Kennedy agreed, mentioned Issenberg. “It ended up being an astronomical number — I wouldn’t say that nobody blinked, because we knew it was an astronomical number — but somewhere in the bowels of the accounting department, they figured out how to pay.”

But Kennedy was not, staffers mentioned, a strolling checkbook or a dissociated nepo child. “John was a great editor, and I’m gonna tell you why,” mentioned DePaulo. “He wasn’t a line editor, like the kind of guy who took your copy and made marks all over it. He was a visionary editor, which is much more important for a good writer.”

“Often we’d be in a meeting with six or eight editors who had come from some great magazines,” Issenberg mentioned, “and John would crystallize a story before anybody else did. That was all from instinct, curiosity, being a smart person and a sharp reader — not the result of any formal training or coaching.”

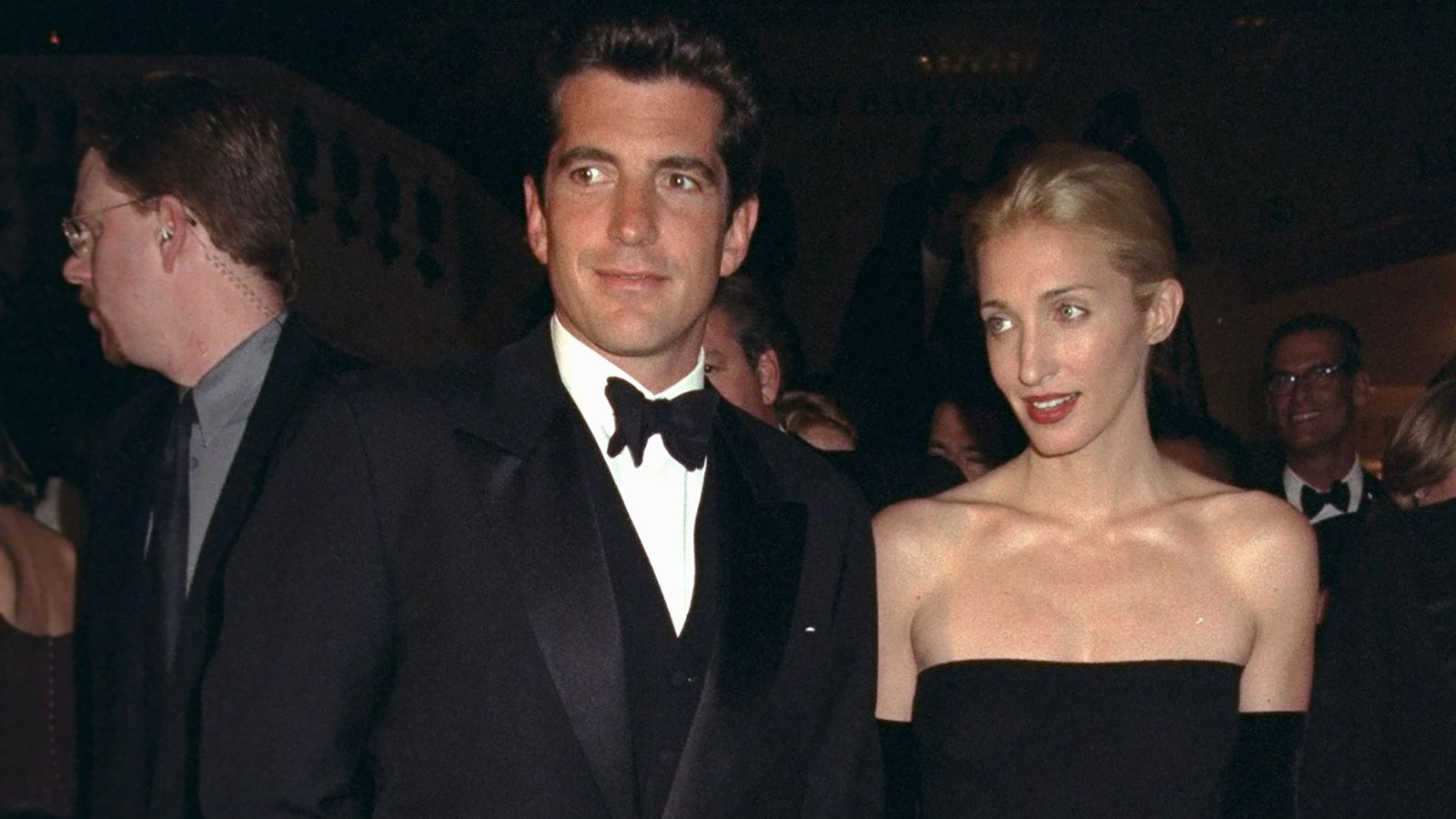

The secret behind JFK Jr. and Carolyn Bessette-Kennedy’s timeless fashion

The pantheon of journal editors have been themselves accustomed to a model of the scrutiny that Kennedy had confronted his entire life. They have been lined each as enterprise figures by a then-aggressive business press and as characters within the gossip columns.

“Condé Nast editors were the original influencers, their lives a top-to-bottom marketing campaign for the company that hired them,” wrote Grynbaum in his historical past of the corporate.

“We were selling a fantasy, a lifestyle, and that crossed over into the real world and our appearances. We were expected to be walking billboards for the fantasy we were selling,” wrote Dana Brown, a journal editor who began because the assistant to Vanity Fair’s Graydon Carter, in his memoir “Dilettante.”

“When I was the editor of Us Weekly, I was written about all the time, for better or worse, in Page Six, and I was not alone,” mentioned Min. “It was the comings and goings of magazine editors who were sort of viewed as like a royal class in New York City.”

The scrutiny might really feel prefer it was coming from in all places on a regular basis. “Every publication had someone who was obsessing over the magazine industry,” mentioned Min, who usually had the perfect fame of any journal editor. “There was someone named Keith Kelly, who worked at the New York Post, whose Media Inc. column was feared. There was Gabriel Sherman and Gabriel Snyder too, people who worked at the New York Observer. There was Jacob Bernstein at Women’s Wear Daily. And so you would come back to your office and you would see a message from one of them, and you’d be like, ‘Oh, crap, now what?’ It could be anything, like your newsstand sales were down, that maybe they’re talking to someone else for your job, that we’re hearing that SI Newhouse” — the proprietor of Condé Nast — “exiled someone to the wrong table at the holiday party, which means they’re on the outs.”

As in all industries within the hysterics of extravagance, the funds have been distributed unequally. “I’m not sure it was that lucrative a time unless you were in the 0.5% of the industry,” mentioned Stephen Rodrick, a longtime journal author. He obtained his begin making $200 a week as an intern at The New Republic in Washington, DC.

He did, nonetheless, receives a commission $10,000 in bills as soon as for a story for George journal. “George went out of business before I could do my expenses and I remember having $2,000 left over. It became my severance package.”

“Look up what journalist salaries were in the 1990s. They were not huge salaries, except for a very small number of people, maybe at a place like Vanity Fair. But I wasn’t at Vanity Fair in the ’90s. I was at New York magazine. We were paid very middle-class kind of salaries,” mentioned Sales. “The story that I lived and that I knew was not about money or excess. It was more like, just cool people who had a lot of talent or just were interesting, and they were just gathering in these nightclubs and having fun and dancing.”

It was this vibe, not the messy open vein of continually flowing cash, that made journal life so charming.

“It could be a nice middle-class living with the tradeoff that you weren’t chained to your desk and got to go to interesting places and meet interesting people,” Rodrick mentioned. “I might write about the making of a Fiona Apple record at Abbey Road one month and then do a true crime saga and then profile a boxer.”

“This is the kind of glamour I’m talking about, when New York was just full of interesting, stylish, talented, beautiful people, and nothing was staged, and everything was real, and you just were covering it for a magazine. It had nothing to do with money or salaries or expense accounts,” mentioned Sales. “The glamour was just being in the game. It was just being in the game and having those little business cards that said New York magazine or whatever.”

Sales did lastly go to Vanity Fair in 2000, the place Graydon Carter “hired me when I was eight months pregnant, and I had the baby, and five days after I had that baby – five days after I had that baby! – I was in a car going out to the Hamptons to do my first story for Vanity Fair on a girl nobody had ever heard of named Paris Hilton. With my baby beside me in a little basket!”

The finish of George and the tip of glossiness

Kennedy died in July 1999. George outlived him for a whereas, dropping “close to” $10 million in 2000, and at last shuttering in March 2001.

“When he died, I kind of knew in my gut that without him, there’s no magazine,” mentioned DePaulo. “But I wished it had gotten to the point that he wanted it to be, which was that it would live without him.”

“The magazine could have this — John liked to say — post-partisan worldview, and could generally treat politicians as noble people trying to do a good job and have fun with sometimes silly things,” Issenberg mentioned. “I don’t think that would have survived 9/11 — which was only eight months after the magazine folded — let alone the financial crisis, or the Trump years or backlash to Obama. It would just be very hard to write about current politics with that sense of amusement and detachment, because the stakes have gotten so high.”

“We were launching a quote ‘post-partisan’ magazine at the very time that the country was fracturing,” mentioned Ginsberg.

“John was ahead of his time,” mentioned DePaulo. “George was ahead of its time. Now, the intersection of politics and pop culture is in every publication.”

“It was, as it turned out, the moment before the end,” mentioned Andersen. “But, boy, what a moment before the end. The end being the internet, obviously.”

Because it wasn’t lengthy earlier than the remainder of the business met comparable roadblocks. Condé started to get a dose of actuality when it launched a journal known as Portfolio, envisioned as a high-flying enterprise title, in 2007. After the corporate spent a 12 months and a fortune making ready to launch it it, it lived for 2 years. “All I did for a year was go to extremely expensive restaurants and woo people to write for us,” editor Jim Impoco informed Grynbaum. He gained 25 kilos.

“I don’t think the company could ever recover from the recession in 2008. And it was just a slow decline from there,” mentioned Odell.

Writers additionally obtained an excellent shorter brief finish of the stick. Steady jobs changed into gig work, paid by the piece. “We stopped getting salaries at Vanity Fair a long time ago, I think it was maybe 2009, after the financial crash. I don’t know about the other Condé Nast magazines, but we stopped getting a monthly check,” mentioned Sales.

A complete host of magazines shuttered, went digital, stuttered, burned out. “I’m sorry to say magazines mean nothing today,” mentioned Jann Wenner, former proprietor of Rolling Stone and Us Weekly, in 2023.

Some of what as soon as was marches fabulously on, adjusted to a newer world. Vanity Fair nonetheless throws its massive Oscars celebration; Bon Appetit flourished as a meals video firm for a while; the New Yorker truly makes cash; Vogue operates profitable digital video franchises; Teen Vogue ran to the ramparts of the youthful revolution; The Atlantic is now the final publication that has determined to vigorously spend its manner into a way forward for significance. Only time, and the huge pockets of the journal’s backer Laurene Powell Jobs, will inform how that story ends.

The identical magazines that would as soon as make or break a designer or an writer, announce a new star, or dictate what we’d all be sporting a few months later immediately have a fraction of that affect. This week Vanity Fair fired its chief movie critic and two writers who lined Hollywood and shut down its weblog — which was run by the identical editor who first wrote about Condé’s elaborate mortgage items for editors practically 20 years in the past.

Vogue, at the very least, stayed in energy by leveraging the smarts and fame of Wintour. That fame has extra to do now with the profit she hosts and dominates every year, whilst hypothesis about her departure from the journal swirls nearly month-to-month. The affect of the journal has floated away from and above the month-to-month bundle of printed paper. “Now it’s less about the Vogue cover and what that’s saying about fashion or culture and now more about the Met Gala and how that can provide a temperature read on culture –– that’s kind of Anna’s way of showing these days who’s in and who’s out, what’s in and what’s out,” mentioned Odell.

“Social media, which has all its ails, of course, and some could argue, has had an incredibly detrimental effect on society, also did something great, which is that it democratized information — and the role of the gatekeeper has completely diminished,” mentioned Min. “Magazine editors were celebrities, which seems almost comical today, but you were really running through the information and the kinds of information that we’re getting to the public through a pretty tight funnel. And that funnel” — which she described as “overwhelmingly white and overwhelmingly male” — “was pretty much reflective of wealthy people who live in Manhattan with a view of what the world wants to read and consume, and setting an agenda that definitely was not one-size-fits-all.”

Kennedy’s human curiosity took him past that body. He wished to attraction to individuals who didn’t match the everyday demographics for political magazines — ladies, younger individuals, Americans in the course of the nation — and he delighted in tales that embodied the perfect of what politics could possibly be, DePaulo mentioned. She remembers that he requested her to write down about her small-town hometown mayor who fastened potholes and chased skunks out of residents’ yards.

Instead of a post-political journal, the world obtained post-magazine politics. Kennedy’s instincts about politics and tradition converging proved to be spot on: Donald Trump, who was on the quilt of George’s March 2000 subject, understood this acutely and catapulted his celeb and affect to 2 presidential phrases.

Trump nonetheless places himself on fake magazine covers for validation, however some model of his celeb and affect — and the attendant and unnerving public scrutiny — is now out there to anybody who desires it.

“Everybody’s a reporter now, and I’m not saying that in a totally disparaging way,” mentioned Sales. “It’s not necessarily a bad thing, completely. It’s interesting to see what people come up with, and they go around and record life as it’s happening and put it on social media. Whatever. It’s just where we are now.”