NCS

—

Across the previous Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc, enormous concrete complexes stand as testomony to Europe’s post-war housing drive. Constructed en masse in the second half of the twentieth century, their utilitarian designs had been often geared towards offering properties as shortly and cheaply as attainable.

But whereas a few of these developments have since been razed or fallen into disrepair, many have outlived the communist governments that constructed them.

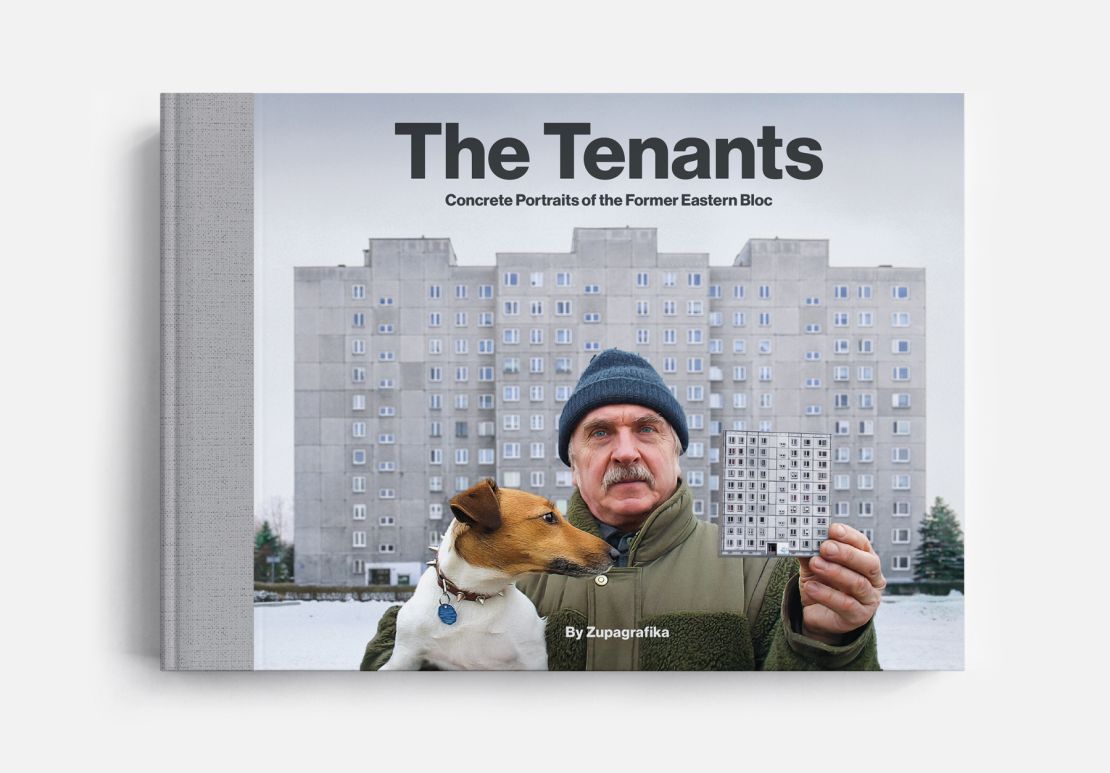

In 2012, David Navarro and Martyna Sobecka, founders of the publishing home and design studio Zupagrafika, started documenting Eastern Europe’s getting old concrete blocks – and assembly the individuals who nonetheless name them house. Initially, the pair supposed to {photograph} paper architectural fashions in opposition to the buildings they represented, although they as a substitute requested residents to pose for portraits holding the illustrations.

A decade later, and with the assistance of photographers from throughout the area, they’ve printed photographs and tales from 40 housing initiatives in 37 completely different cities.

From what was as soon as East Berlin to the distant Russian metropolis of Norilsk, Navarro and Sobecka discovered that occupants of those often-reviled buildings complain of points together with poor insulation and lack of upkeep. But additionally they found many residents who had been complimentary and nostalgic about their Cold War-era properties.

As the pair write in the introduction to their new e book, “The Tenants: Concrete Portraits of the Former Eastern Bloc,” their topics have recollections of each “the buildings’ golden years and darker times.”

Barbara, Plac Grunwaldzki housing property in Wrocław, Poland (pictured prime)

“I used to be one of many first tenants right here. I completely love my condo on the fourth ground. I’ve three spacious rooms with a small kitchen.

“The only disadvantage is the pigeons, oh dear, that’s really terrible! The renovation looks pretty and clean on the outside but they didn’t lay ceramics on the balcony floors, as they promised. Besides, the tenants are still paying about 200 zloty ($43) a month each for this renovation.”

“These panelák (pre-fabricated concrete) homes had been constructed in a short time so that individuals had locations to dwell. Everybody favored it right here. Then the Velvet Revolution got here they usually wished to tear them down; if that they had demolished them, we’d not have properties immediately.

“When we were buying an apartment here it was very affordable, now they are available for 4 million koruna ($166,000), quite expensive for people who don’t have much money.”

“There are almost no young people living here, but the house has a lot of advantages: It is relatively quiet, close to the metro and there is plenty of greenery around. The main disadvantage is that the walls, floors and ceilings are uneven. Probably something went wrong during construction.”

“I’ve lived on the bridge ground for 40 years. Before the bridges had been constructed, the whole ground was closed down and I used to be the one one staying there.

“These rounded windows used to be balconies which couldn’t be transformed back then. Now, some of the tenants have covered them up to have more heated room inside, only their exhaust fumes rise up to my balcony.”

“The buildings are old and well-constructed. They are the statues of Belgrade. Their foundations are deeply grounded protecting even higher floors from earthquakes.”

“I used to be born in (the japanese district of) Prenzlauer Berg and moved right here in the Seventies. I dwell on the ninth ground and I’ve a two-bedroom condo, greater than sufficient room for me and my canine.

“The rent is 500 euros ($511) a month and for my modest pension it is quite a lot, but it isn’t much for this great location, is it? I can see the Television Tower from my window!”

“The Tenants: Concrete Portraits of the Former Eastern Bloc,” printed by Zupagrafika, is accessible now.