To guests, Venice is an excellent tapestry of historic buildings, waterways, bell towers, purple roofs — and a mighty winged lion, the image of the Venetian republic, carved into constructions throughout town.

Possibly essentially the most famous model of the lion is a bronze statue standing atop a column within the Piazzetta adjoining St. Mark’s Square — and now, researchers suppose the statue was made in China.

After learning samples from the metallic lion utilizing lead isotope evaluation, researchers from northern Italy’s University of Padua discovered that the copper used to create the bronze alloy (which is a mixture of copper and tin) on the unique bronze work got here from the Yangtze river in China, in response to a examine printed within the journal Antiquity on Thursday.

This, they stated, would clarify why the 4-meter- (13-foot-) lengthy and a couple of.2-meter- (7-foot-) excessive statue, beforehand thought to have been made domestically, in Syria or Anatolia, is stylistically mysterious.

Although it was put in in St. Mark’s Square within the thirteenth century, the lion extra carefully resembles work produced in China through the Tang Dynasty — 618 to 907 AD — than that present in medieval Mediterranean Europe, the researchers argue, citing the form of its snout and scars from the elimination of earlier horns.

The column on which the lion stands is from Anatolia (a part of modern-day Turkey), and the lion itself has been repaired a number of occasions, with the earliest recorded occasion in 1293.

“It is possible that Marco Polo’s father and uncle, during the four years they spent at the court of Kublai Khan during their first journey, were responsible for the acquisition of the sculpture,” the researchers stated, including that the go to probably came about between 1264 and 1268.

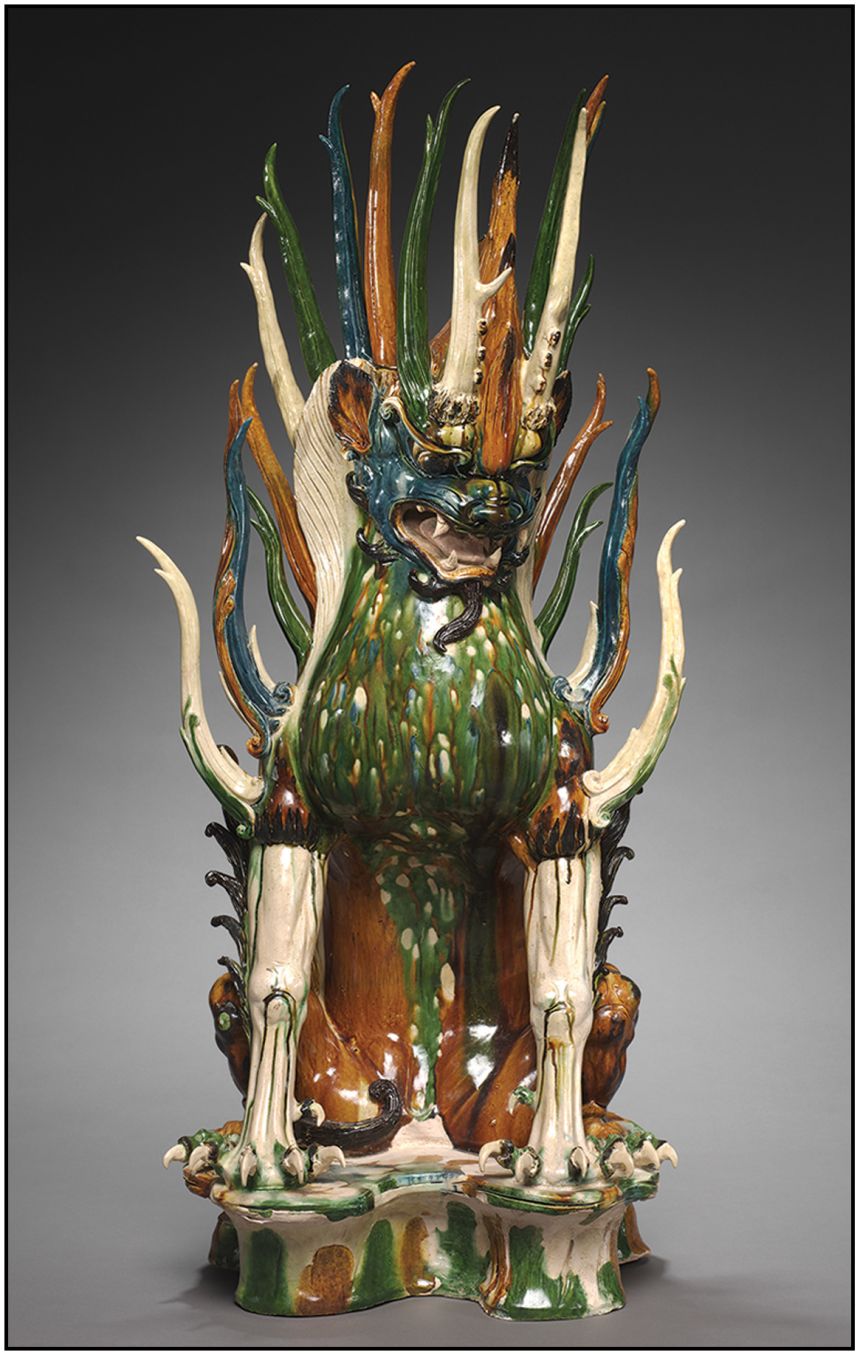

The animal was initially a zhènmùshòu, a monumental, fierce, lion-like tomb guardian from the Tang Dynasty, the authors speculate.

Once the Polos despatched the statue again to Italy after their go to to the Mongol court docket, it was in all probability “discreetly and laboriously refitted” to appear like the holy emblem of St. Mark, with horns eliminated and a “wig” added, they added.

“In a puzzling absence of written information, the intention and logistics behind its journey to Venice remain elusive and open to interpretation. If the installation of the ‘Lion’ was meant to send a strong, defensive political message, we can now also read it as a symbol of the impressive connectedness of the medieval world,” they added.