As so often happens in science, when Andrea Stöllner’s experiments did not work as anticipated, they led her to one thing much more attention-grabbing – a option to research what is perhaps the preliminary spark of lightning, utilizing lasers and a single microscopic particle.

Stöllner, a physics researcher from the Institute of Science and Technology Austria, headed a research with a global workforce of researchers right into a known but little-understood ability for light-based ‘tweezers’ to cost particles of their grasp, giving researchers a brand new option to examine one of nature’s most majestic phenomena.

How lightning begins is one of the biggest mysteries in atmospheric science. There are a number of theories, which all attempt to clarify what kicks off {the electrical} cascade inside clouds that culminates in a lightning bolt.

Nearly 9 million lightning bolts illuminate Earth on daily basis, zigzagging through clouds for hundreds of miles in essentially the most excessive circumstances.

Related: World’s Longest Lightning Strike Crossed 515 Miles From Texas to Kansas

And but, contemplating how a lot we all know concerning the physics of distant objects within the far corners of the Universe, it is stunning we do not know what triggers lightning inside clouds just some kilometers above our heads.

Scientists have despatched up climate balloons to measure circumstances inside thunderclouds, flown plane via storms, and used high-speed cameras and sensors to seize lightning strikes – and the photonuclear reactions they set off.

But exactly how lightning begins stays an open query.

Thunderclouds turn into highly charged; that a lot is thought. The main principle is that ice crystals inside clouds turn into charged once they collide with a kind of tender hail known as graupel; the opposing expenses separate, creating an electrical area.

frameborder=”0″ permit=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>

There’s just one problem. The electric fields measured inside clouds are relatively weak; nowhere close to robust sufficient to turn air into a conductor via which present can circulation.

“This suggests that there’s both one thing mistaken with our measurements,” Joseph Dwyer and Martin Uman, two lightning scientists, wrote in 2014, “or there’s something mistaken with our understanding of how electrical discharges happen within the thunderstorm surroundings.”

It might be that there are pockets of higher intensity electric fields inside clouds that scientists haven’t found yet, or that ice crystals somehow create the first spark that lightning needs to start, Stöllner told ScienceAlert.

High-energy cosmic rays are another possibility: They may ionise the air, creating a shower of free electrons that claps into a lightning bolt.

“But then once more,” Stöllner says, “it is also one thing fully completely different or a mix of all of these issues; we do not know.”

The theories about how lightning begins have been floating round since the 1950s and 60s, primarily based largely on observations and pc simulations, and barely examined in lab experiments.

Stöllner didn’t set out to study how lightning starts, but that’s where her research is headed.

“I believe now is an efficient time to revisit this query as a result of we have now the expertise to do it,” says Stöllner, a PhD student in the labs of physicist Scott Waitukaitis and climate scientist Caroline Muller.

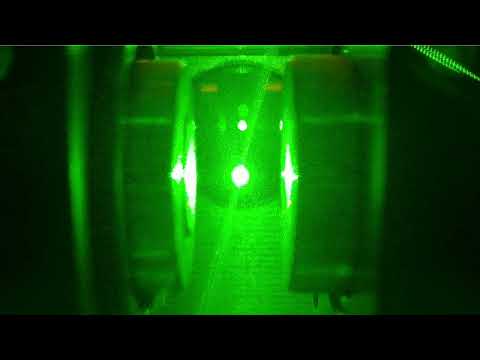

In their recent study, Stöllner and her colleagues used lasers to ‘trap’ a single, microscopic particle of silica and measure the particle’s charge with an increase in the laser’s intensity. As the neutral silica particle accumulates charge, it ‘shakes’ in the alternating electric field across the laser.

The team’s measurements suggest the neutral silica particle likely absorbs two photons from the laser, which energises and liberates electrons, leaving the particle positively charged.

frameborder=”0″ permit=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>

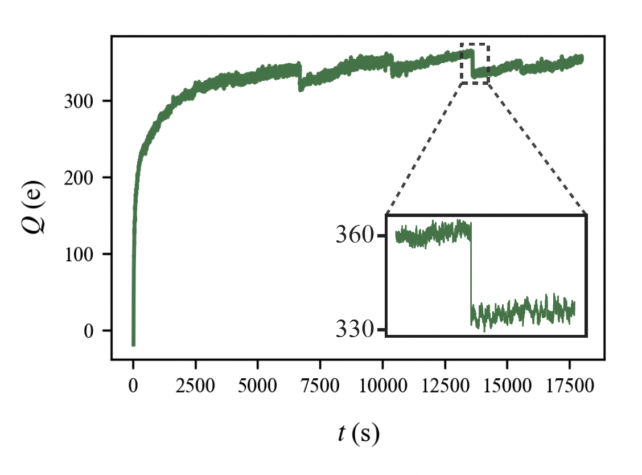

But Stöllner additionally observed one thing sudden: Sometimes, when a particle was trapped for weeks, it abruptly stopped shaking as a lot – a spontaneous discharge, which, if it have been to happen within the environment, would possibly set off one thing bigger, like a lightning bolt.

“We don’t know how it happens, but basically the charge just drops very quickly,” Stöllner says. “We’re very interested in just finding out what causes that, and that is actually pretty much the same question as lightning initiation, just on this tiny, tiny scale.”

The lightning hyperlink is extremely speculative at this level, so Stöllner continues to be finding out the discharges and testing whether or not particle dimension, humidity, or stress has any impact.

“In one way, it’s a limitation of our study because everything is super tiny and super small, and 10 electrons doesn’t make lightning,” Stöllner says. “But on the other hand, it’s a very high-resolution way to probe this charging and discharging of a single particle.”

Dan Daniel, a physicist at Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology in Japan, who was not concerned within the research, informed ScienceAlert that the power to entice a single submicron particle, cost it controllably, and measure its cost “with exquisite resolution” is “genuinely impressive”.

“This is exactly the level of precision needed to eventually probe the charging of water droplets or ice particles – an essential step toward a truly microscopic understanding of lightning, cloud electrification, and atmospheric electricity,” Daniel defined.

frameborder=”0″ permit=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>

The method is more realistic in some ways because it doesn’t use metal electrodes to measure charge. Instead, the particles hover in the air like aerosols in the atmosphere.

It also uses weaker electric fields than previous lab experiments, Stöllner says.

However, ice crystals in clouds, not aerosols, are thought to be the main players in lightning initiation, and they are complex and strange in their own ways.

Daniel also points out that the sunlight that hits Earth’s atmosphere is much weaker than the lasers used in these experiments. There is some evidence, however, that dust particles and aerosols can become charged under UV rays – likely via a single-photon rather than multiphoton process, Daniel says.

Dust on the Moon, which will get bombarded with UV mild and photo voltaic winds, additionally becomes charged and levitates, clogging up lunar rovers and devices.

So the experimental framework is related “not only for lighting and cloud electrification,” Daniel says, “but in addition to issues in planetary science and house exploration.”

The research has been revealed in Physical Review Letters.

Research for this text was partly supported via a journalism residency funded by the Institute of Science & Technology Austria (ISTA). ISTA had no enter into the story.