Editor’s Note: Read extra unknown and curious design origin tales here.

NCS

—

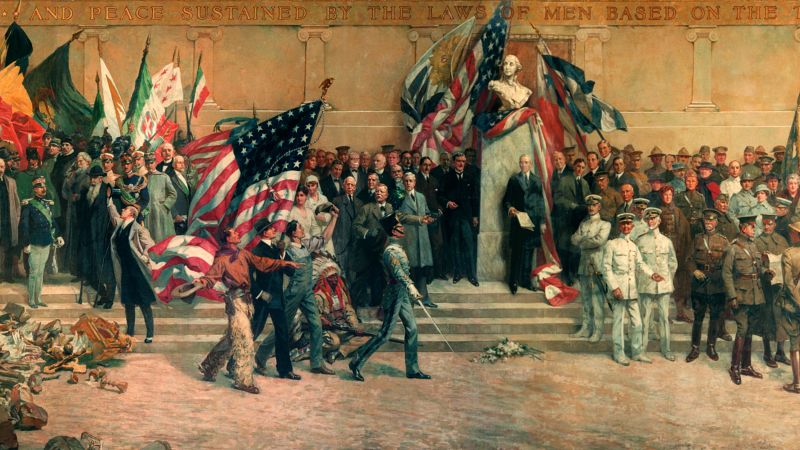

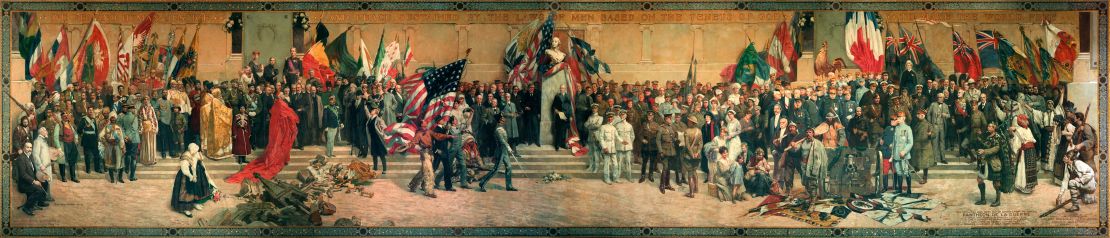

Less than a month earlier than the tip of World War I, an enormous painting commemorating the battle effort was unveiled in central Paris. Its creators wished to honor the best battle the world had ever seen with the best painting ever made, they usually had spent the earlier 4 years engaged on it with the assistance of 150 artists.

The end result was the world’s largest painting on the time, set on a panoramic canvas measuring 402 ft (122 meters) round and 45 ft (13.7 meters) excessive. It contained over 5,000 life-size portraits of battle heroes, royalty and authorities officers from the Allies of World War I, with France dominating the stage. The painting was so large {that a} {custom} constructing needed to be constructed to accommodate it.

The “Panthéon de la Guerre” (which means “Pantheon of the War”) was unveiled, to nice fanfare, on Oct. 19, 1918. In the century that adopted, it was chopped up, auctioned off, hidden away and even saved open air in a crate for a decade earlier than discovering its place on the partitions of the National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri, 4,500 miles away from the beginning of its unlikely journey.

Work on the painting had begun, with astonishing foresight, just some months into the battle, within the winter of 1914. The concept got here from two French artists with earlier expertise in panoramas, Pierre Carrier-Belleuse and Auguste François-Marie Gorguet.

Together, they enlisted an array of painters – significantly aged ones, as many younger ones had been on the entrance line – and obtained monetary and political help, which was important as a result of scale of the challenge and the supplies required. Among the latter had been 18,000 sq. ft of Belgian linen for the canvas, tons of metal armature to help it and large quantities of paint, all of which had been at a premium in wartime.

“Their intent was patriotic, but also commercial,” mentioned Mark Levitch, an artwork historian on the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and writer of “Panthéon de la Guerre: Reconfiguring a Panorama of the Great War,” in a telephone interview. “Panoramic paintings like this were money-making ventures – the Hollywood blockbusters of the day. But it was really a 19th-century phenomenon, and this was sort of its last gasp.”

The painting was hung in a whole, uninterrupted circle; guests descended right into a tunnel to emerge proper within the center of it. The custom-built, octagonal constructing that housed it was enviably situated in Rue de l’Université, steps from Les Invalides and just some blocks from the Louvre. It was inaugurated by French President Raymond Poincaré, himself immortalized on the canvas, lower than a month earlier than the tip of the battle – timing that was “mostly serendipitous,” as Levitch places it.

Although a round painting has, technically no middle, the principle focus of the “Panthéon de la Guerre” was a temple and staircase, representing the French part that spanned about 122 ft. This phase contained most of the 5,000 figures portrayed within the painting, with the remainder break up between different Allied nations together with Britain, Italy, Russia and the United States, every given an area of round 32 ft or much less. The background was meant to characterize the battlefields of France and Belgium.

The seek for figures worthy of showing within the paintings was painstaking.

“They sifted through the press and read the citations of the day, to see who was killed and find out who was most deserving of being put in this sort of encyclopedia of the French war effort,” Levitch mentioned. “They got photographs of people who had been killed and made sketches from those, while others, such as government officials, were sketched in person.”

Infrared pictures retell horrors of D-Day

The “Panthéon de la Guerre” remained in its Paris dwelling for 9 years and was seen by three million individuals. “It was as much for tourists as it was for the French, and seemed particularly popular with American soldiers,” Levitch mentioned.

In 1927, as curiosity began to wane, it was purchased by three American businessmen who wished to ship it on a US tour.

“I think they bought it for something like 250,000 dollars, real money for the time, and it had a very high-profile sendoff that I suspect was meant as much for American eyes as it was for the French,” Levitch mentioned.

The creators of the painting had been against the sale, fearing they’d by no means see it once more, though the patrons promised to finally return it. The sendoff concerned ambassadors and bands taking part in nationwide anthems, within the hope that the “Panthéon de la Guerre” would cement Franco-American relations. A number of modifications had been made, most notably the inclusion of extra ladies and African-Americans.

Its first cease was New York’s Madison Square Garden, the place it attracted a million guests in eight weeks. “They had an appropriately gargantuan opening night with 25,000 people and lots of notables, but it ended up closing two months ahead of schedule, so they were obviously not making as much money as they had hoped,” Levtich mentioned.

The painting, similar to the battle itself, was perceived very in a different way within the US. France had suffered about 1.7 million deaths within the battle, whereas the US, which entered the battle in 1917, misplaced round 117,000. Americans had a faint, largely celebratory reminiscence of the battle; the French a reasonably vivid, bloody one.

“It was not promoted as the solemn painting that it was,” Levitch mentioned. “Instead, there were blow horns and even machine guns in Chicago for the 1933 World Fair. It was almost like a carnival attraction, but that’s not the spirit of the painting at all. It’s really rather quiet for all its grandiosity.”

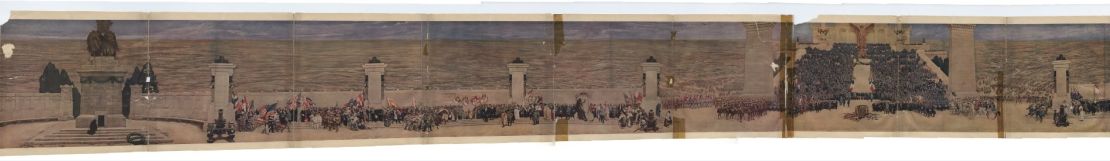

The final cease on the painting’s US tour was San Francisco in 1940. At that time, the paintings was falling out of trend and was despatched to a storage facility in Baltimore, the place it laid deserted for 12 years within the virtually tomb-like, 55-foot crate initially constructed for it in Paris. Because the painting was too large to maintain indoors, it was left exterior, and as soon as the proprietor stopped paying the storage price – because of being caught up in World War II in Europe – it was auctioned off.

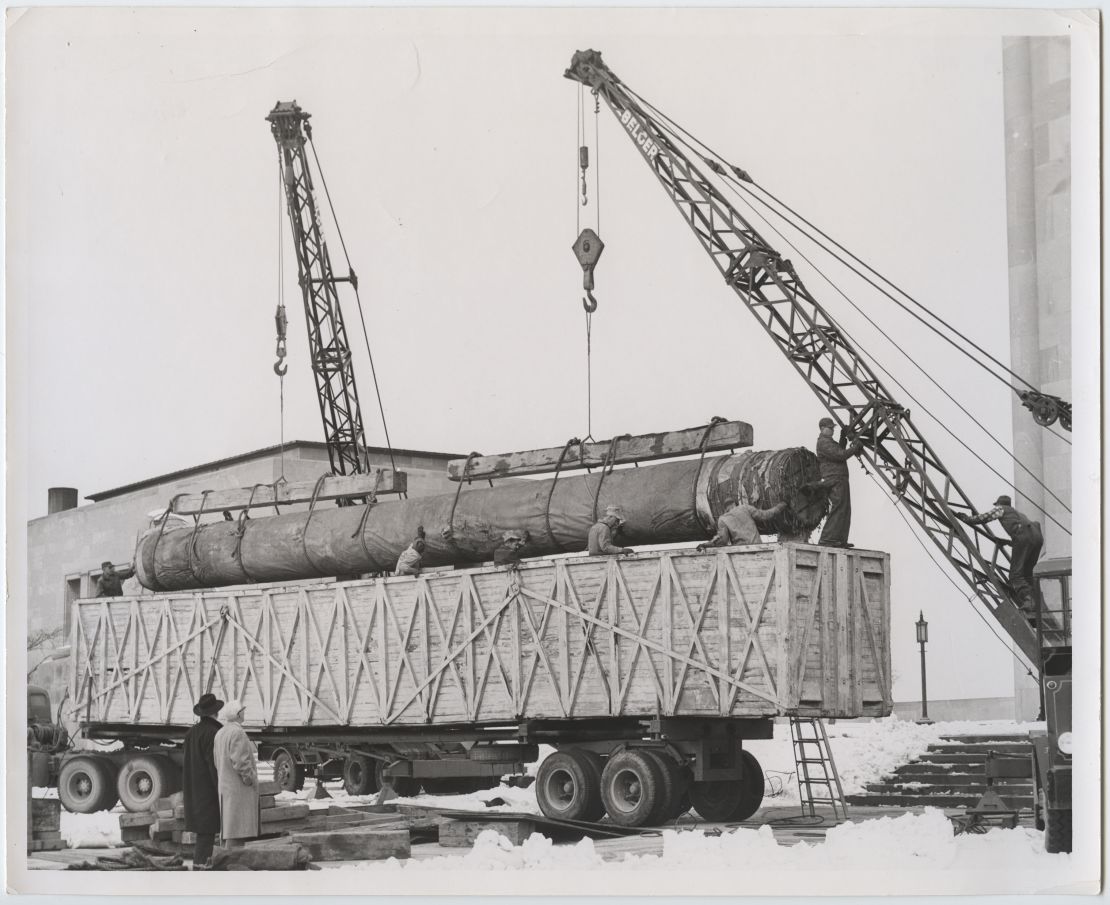

The public sale befell in July 1952 and included each the painting and the equipment required to exhibit it, weighing in at a considerable 10 tons. But though the public sale data offered it as “an art object of unusual value,” few artwork connoisseurs confirmed up and the “Panthéon de la Guerre” went for a paltry $3,400 (round $32,000 in immediately’s cash) to William H. Haussner, an area restaurateur who was additionally an artwork collector and, by the way, a German World War I veteran.

“He owned a restaurant in Baltimore (that was) very well known for having good art and bad art – mostly bad art – on its walls,” Levitch mentioned. “He gets word that this was, at one time, an important artwork, and he doesn’t want it to go to the scrap metal collectors who were there to get the armature for the painting – that’s who he was competing against in the auction.”

Opening the large crate was such a large operation – 22 employees and a 48-foot trailer truck had been concerned – that Life magazine sent reporters to document it. But even with a brand new proprietor, the long run regarded bleak for the painting.

“Haussner tried to find a museum that was willing to take it. He got in touch with the Smithsonian. He was willing to donate it but, unsurprisingly, nobody wanted it. Nobody wanted to create a building for it, or repair it. Even the French Consulate said they didn’t want it back. It wasn’t considered ‘high’ art,” Levitch mentioned.

But there was one one that wished it: Daniel MacMorris, himself a US World War I veteran who had seen the painting in Paris through the battle. He had even gone on to review with Gorguet, one of the 2 authentic creators, and was now knowledgeable artist. Awestruck by the Life journal article, MacMorris began lobbying Haussner to donate the painting to the Liberty Memorial in Kansas City, the nation’s largest World War I memorial, the place he labored.

Haussner finally agreed, giving the “Panthéon de la Guerre” a second life. It wanted to be tailored for its new venue, and MacMorris took on the duty. “But he knew that he was not going to be able to save the entire painting, that was actually never his intention,” Levitch mentioned.

MacMorris had 70 ft of wall house to work with, and, as he wrote in a 1958 letter to the London Daily Telegraph, he wished to pay homage to Woodrow Wilson and the League of Nations, the precursor to the UN. But his “rearranging,” as he referred to as it, is greatest recognized for being US-centric – with few Russian or Eastern European figures making the minimize – and for maintaining virtually nothing of the unique canvas.

“In terms of square footage, he kept only 7 percent of the original, and also made it into a regular painting that’s totally flat against the wall,” Levitch mentioned. “He ended up repainting a lot of figures and it looks really good. It’s impressive work and it only took a couple of years.”

The new, Americanized model of the painting – which now included Harry Truman and Franklin Roosevelt, amongst others – was unveiled in Kansas City on Nov. 11, 1959.

“MacMorris centered it on the US,” the museum’s archivist, Jonathan Casey, mentioned in a telephone interview. “He put Woodrow Wilson and all the American political and military leaders in the center, with the Allies on either side – the whole ‘Panthéon’ scene with all the French soldiers was just totally removed. You get a whole different sense from it, with America dominating and coming out (looking) most responsible for the victory.”

The Liberty Memorial closed down within the 1994 because of security considerations round its ageing construction, however after a profitable renovation it opened once more in 2006. In 2014 it was acknowledged as a nationwide memorial and adjusted its title to National World War I Museum and Memorial. “The renovation really paid off, and it has made the museum incredibly popular and always crowded,” Levitch mentioned. “And people are now paying more attention to the Panthéon and its incredible history.”

But what occurred to the remainder of the unique painting? A big portion of the unique French part now hangs in one other corridor on the museum, which additionally retains dozens of smaller fragments in its archives and exhibits essentially the most important ones. MacMorris threw away giant parts of the canvas, however he additionally doled out items to buddies and acquaintances. Some have ended up in flea markets and on-line, the place Levitch bought one in 2001. “I spotted it on eBay, but it was not advertised as ‘Panthéon de la Guerre.’ It’s a very tiny fragment, about two feet tall and a foot wide,” he mentioned.

“I bought it for 99 dollars, which is more than it’s probably worth, but to me it was important.”