London

NCS

—

There is one thing peculiar about getting into a constructing solely to be greeted by one other one inside it, so it takes a second to regulate upon arriving on the second ground of London’s prestigious Tate Modern artwork gallery. Directly in entrance of the entryway is a 1:1 scale facsimile of Do Ho Suh’s childhood residence in Seoul, which he wrapped in mulberry paper and punctiliously traced in graphite to provide an intricate rubbing of the outside. It is only one of many variations of residence envisioned by the Korean artist over the previous 30 years.

Running at Tate Modern by means of to October, “Walk the House” is Suh’s largest solo institutional present to this point within the UK, the place he has been based mostly since 2016. Before that, he lived within the US, having studied on the Rhode Island School of Design and Yale University within the Nineteen Nineties.

The exhibition’s title stems from an expression used within the context of the “hanok,” a conventional Korean home that may be taken down and reassembled elsewhere, because of its development and light-weight supplies. The buildings have turn into rarer over time, due to urbanization, struggle and occupation, which led to the destruction of many conventional houses within the nation.

Suh’s personal childhood residence was an outlier amid Seoul’s altering cityscape in the course of the Seventies, which underwent fast growth after the Korean War left the town in ruins. It spurred the artist’s ongoing preoccupations with residence as each a bodily area that could possibly be dissolved and reanimated, but additionally a psychological assemble that may replicate reminiscence and id.

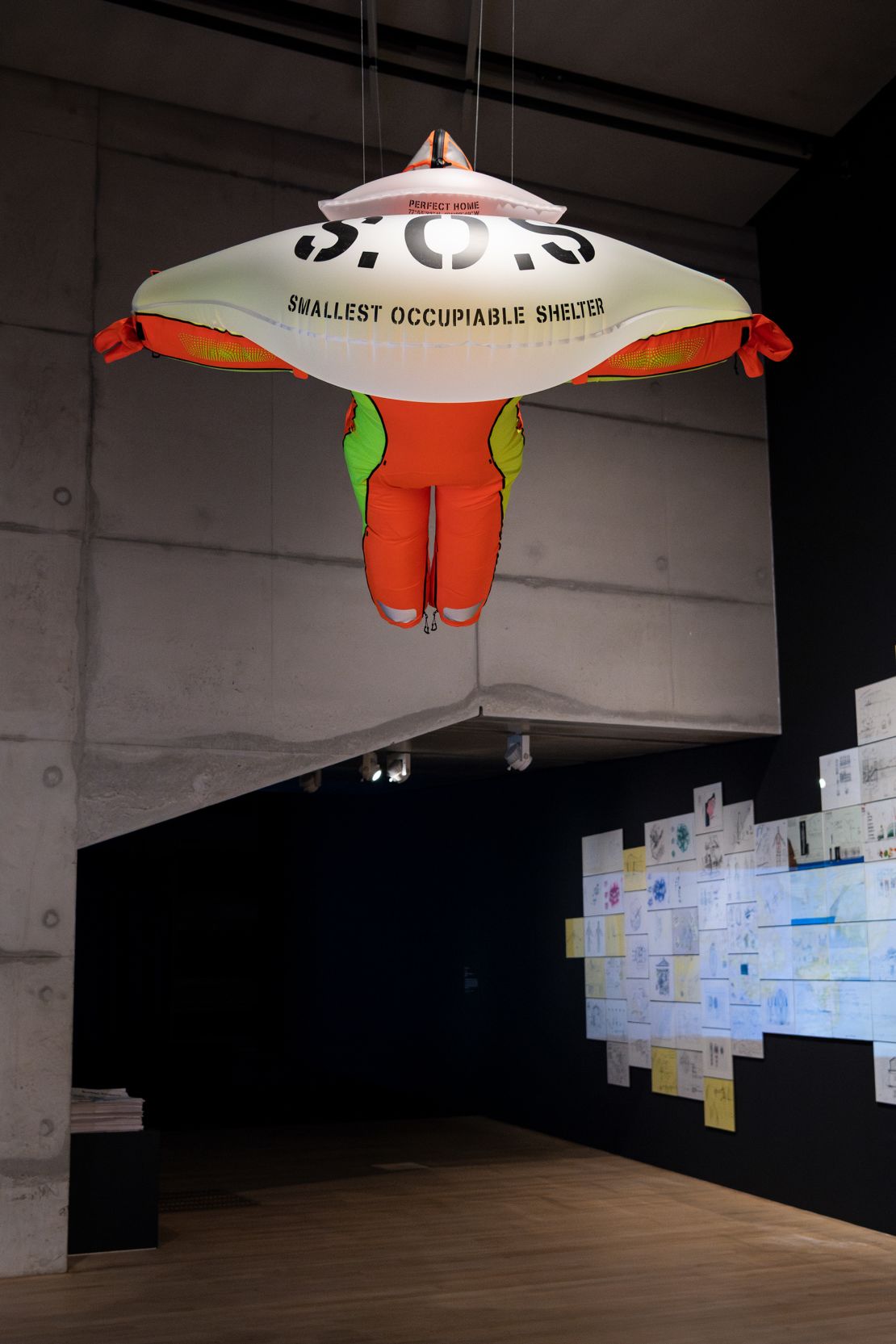

Among the present’s reveals are embroidered artworks, architectural fashions in varied supplies and scales, and movie works involving complicated 3D methods. The detailed outlines picked up in Suh’s hanok rubbing are echoed in two intently associated large-scale items on show for the primary time, each of which guests can stroll inside. “Perfect Home: London, Horsham, New York, Berlin, Providence, Seoul” (2024) takes varied 3D fixtures and fittings from houses Suh has lived in around the globe and maps them onto a tent-like mannequin of his London condo. “Nest/s” (2024) is a pastel-hued tunnel, once more based mostly on totally different locations he has known as residence, this time splicing collectively incongruous hallways — an setting that holds symbolic which means for the artist.

“I think that the experience of cultural displacement helped me to see these in-between spaces, the space that connects places. That journey lets me focus on transitional spaces, like corridors, staircases, entrances,” Suh instructed NCS on the present’s opening. The exhibition additionally options “Staircase” (2016), a 3D construction that was subsequently collapsed into a pink, sinewy 2D tangle. “I think in general we tend to focus on destinations, but these bridges that connect those destinations, often we neglect them, but actually we spend most of our time in this transitional stage,” Suh mentioned.

There’s a translucent high quality to a lot of the work on show. Fine, gauzy textiles are used straight inside lots of the items, in addition to within the type of a refined room divider — the closest factor to an inside wall in the principle area.

“For the first time since 2016, the galleries of the exhibition will have all their walls taken down in order to accommodate the multiple large-scale works that will be materialized within them, as well as the multiple times and spaces that those works carry,” mentioned Dina Akhmadeeva, assistant curator for worldwide artwork at Tate Modern, who co-curated the present with Nabila Abdel Nabi, senior curator of worldwide artwork on the Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational. “In doing so, the open layout will form not a linear passage or narrative, but instead encourage visitors to meander, return, loop back, evoking an experience closer to the function of memory itself.”

Suh’s emphasis on spatial interventions poses artistic challenges for curators in addition to the establishments that maintain these works. One such instance is “Staircase-III” (2010), acquired by the Tate again in 2011, which frequently must be tailored to wherever it’s proven by measuring new panels to suit every area. “I wanted to disturb the habitual experience of (encountering) an artwork in a museum,” mentioned Suh by means of rationalization. Akhmadeeva added that the strategy challenged the “idea of permanence — of the work and of the space around it.”

Removing the gallery partitions additionally displays Suh’s curiosity in peeling environments again to their foundations. “It’s just the bare space that the architects originally conceived,” he mentioned. Suh’s work usually focuses on spatial experiences moderately than materials items as a result of, similar to the rooms and buildings we inhabit, an empty area behaves like a “vessel” for reminiscences, he defined. “Over the years and the time that you’ve spent in the space, you project your own experience and energy onto it, and then it becomes a memory.”

The artist does often concentrate on ornaments and furnishings, nonetheless, as seen in his monumental movie, “Robin Hood Gardens” (named after the East London housing property it captures), which used photogrammetry to sew collectively drone footage taken contained in the council constructing awaiting demolition. It marked a uncommon occasion of Suh documenting each residents and their belongings.

The movie illustrates the refined politics of Suh’s follow. “Often in my case, the color and the craftsmanship and the beauty in my work distract from the political undertone of it,” he mentioned. Issues akin to privateness, safety, and entry to area are intimately related to class and public coverage, however his commentary is roofed in a comfortable veil of material or the light rub of graphite. The latter can also be utilized in “Rubbing/Loving: Company Housing of Gwangju Theater” (2012), which displays on the lethal Gwangju Uprising of 1980. The paintings resembles the shell of a room that’s unravelled to kind a flat, vertical construction, like a deconstructed field. It is predicated on a rubbing that was taken by Suh and his assistants whereas blindfolded — a nod to the censorship of the navy’s violent response and its absence from South Korean collective reminiscence.

The exhibition is bookended by items that tackle sociopolitical questions. “Bridge Project” (1999) explores land possession amongst different points, whereas “Public Figures” (2025), an evolution of a piece Suh made for the Venice Biennale in 2001, is a subverted monument that includes an empty plinth, directing focus to the numerous miniature collectible figurines upholding it. For Suh, it was supposed to handle Korea’s histories of each oppression and resilience. While these two reveals might really feel distinct, for Suh, all of his work interrogates the boundaries between private and public area, and the situations that power transience or allow permanence.

The pressure between private and non-private was thrown into sharp reduction in the course of the pandemic, when lockdowns pressured folks to spend most of their time indoors. Although Suh “scrutinized” all corners of his residence throughout this time, the lockdowns didn’t materialize in his follow in the best way one would possibly anticipate. Instead, it elicited a extra tender reflection on what is usually the making of a residence: folks. It explains why, among the many substantial, usually colourful buildings within the exhibition, there are two small tunics made for (and with) his two younger daughters, adorned with pockets holding their most cherished belongings, akin to crayons and toys.

“As a parent, it was quite a vulnerable situation. Other families, I cannot speak for them, but it really helped us to be together,” mentioned Suh.