EDITOR’S NOTE: This article was initially printed by The Art Newspaper, an editorial accomplice of NCS Style.

In a really uncommon and certain precedent-setting settlement, the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) Boston has agreed to return two works from 1857 by the Black potter David Drake, who made his bold jars whereas enslaved, to his present-day descendants.

By the phrases of the contract, a kind of vessels will stay on mortgage to the museum for not less than two years, in accordance to the lawyer George Fatheree, who’s representing Drake’s descendants. The different vessel — a masterpiece generally known as the “Poem Jar” — has been bought again by the museum from the heirs for an undisclosed sum. Now the work comes with “a certificate of ethical ownership.”

“In achieving this resolution, the MFA recognizes that Drake was deprived of his creations involuntarily and without compensation,” a museum spokesperson stated in a press release. “This marks the first time that the museum has resolved an ownership claim for works of art that were wrongfully taken under the conditions of slavery in the 19th-century US.”

Fatheree goes additional, saying he believes their settlement “is groundbreaking in the art world.”

“The application of principles of ethical restitution to artwork created by enslaved Americans, this is the first time that has ever occurred to my knowledge,” he stated in a video name.

Ethan Lasser, chair of the artwork of Americas on the MFA, stated the museum has realized from its work restituting Nazi-looted artwork. “We’ve become very expert in Holocaust restitution. We’re dealing with (repatriation) issues in our African collections and Native American collections,” he stated over the cellphone. “And we want to bring the same standard to the fullness of our collection.”

He considers Drake’s work an instance of “stolen property,” too, “since the artist is always the first owner of his work and he never got to make the call about where it went or what he was paid for it.”

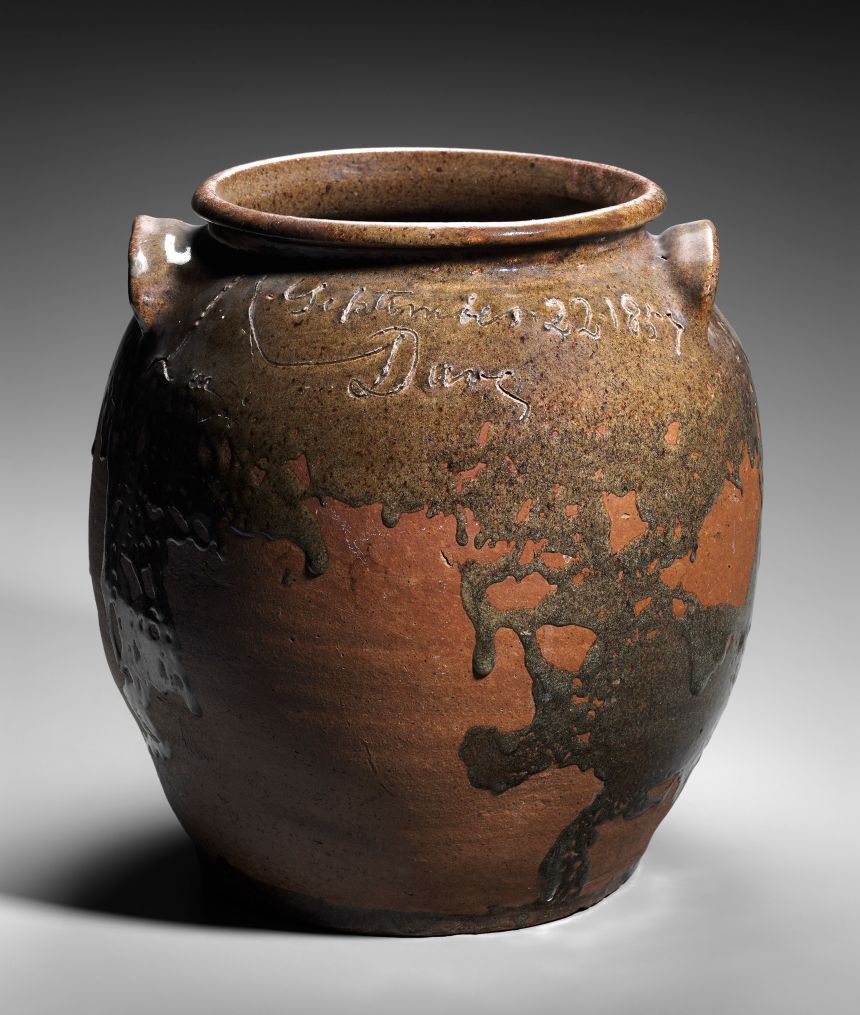

Born enslaved round 1800 in Edgefield, South Carolina, a area recognized for its wealthy clay, Drake (who was also referred to as Dave the Potter) was certainly one of comparatively few African American potters to signal his work. He additionally dared — regardless of punitive anti-literacy legal guidelines for enslaved individuals within the state — to etch quick sayings or poems on the jars, making them highly effective acts of resistance. Some inscriptions boast of the jar’s supposed contents or monumental capability; others comment extra poignantly on his personal life or working situations.

The “Poem Jar,” which the MFA initially purchased in 1997 from a vendor in South Carolina, contains a couplet that hints at Drake’s monetary exploitation. The inscription reads: “I made this Jar = for cash/Though its called Lucre trash.” Currently in a gallery for self-taught and outsider artwork on the museum, it can assume a extra outstanding spot on the entrance of the Art of Americas wing as soon as renovated in June 2026. (The jar that Drake’s household now owns has a signature and date however no writing.)

Another jar made the identical yr, 1857, has a very wrenching inscription in mild of Drake’s compelled separation from a lady believed to be his spouse and her two sons. That vessel, on the Greenville County Museum of Art in South Carolina, reads: “I wonder where is all my relation.”

One of Drake’s great-great-great-great grandsons, the kids’s guide writer and producer Yaba Baker, stated he feels the restitution course of provides one reply to that query. “It’s been exciting, overwhelming and feels full circle,” he stated in a video name. He praised the MFA for “showing integrity and leadership” in “allowing us to connect to Dave’s legacy,” noting that “to go from being slaves to having a family of engineers and doctors and people in executive positions is a testament to Dave’s legacy in a different way.”

These descendants started speaking about getting concerned in Drake’s legacy in 2022, upon the opening of “Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina,” an exhibition collectively organized by the MFA and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The household quickly employed Fatheree, contemporary from his win within the Bruce’s Beach land reparation case. Earlier this yr they established the David Drake Legacy Trust, ruled by 5 of the oldest heirs.

So far there are about 15 relations concerned, in accordance to Fatheree, however they’ve created an internet site in order that different descendants of Drake might be recognized and be a part of the efforts — what Fatheree calls “a big tent approach.”

The initiative’s repercussions may very well be widespread. There are thought to be round 250 pots by Drake nonetheless in existence, and over the previous 5 years the marketplace for his work has exploded, pushed primarily by American museums competing for items within the hopes of telling a extra complicated story in regards to the historical past of slavery within the US. Several have paid six figures for his work, and in 2021 the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas paid a record-setting $1.56 million for a 25-gallon stoneware jar at public sale.

Other museums that personal Drake’s work embrace the Met, the Philadelphia Art Museum, the De Young Museum in San Francisco, the Art Institute of Chicago, Harvard Art Museums, the St Louis Art Museum and the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC, in addition to smaller venues within the American South.

Fatheree confirmed he has begun to attain out to a few of these different artwork establishments on behalf of the household. “Our approach has been one of collaboration and invitation. I am not a litigator; we did not go to the museum and file a lawsuit (or) threaten to sue them. But our hope and frankly our expectation is that other institutions” — and personal collectors of Drake’s work, he added — “will follow the Boston museum’s lead here.”

“This is not just an opportunity for museums to be on the right side of history,” he stated. “It’s an opportunity for museums to rewrite history and think not just about ownership and stewardship, but think about stewardship and justice.”

Read extra tales from The Art Newspaper here.