Patents created by U.S. inventors

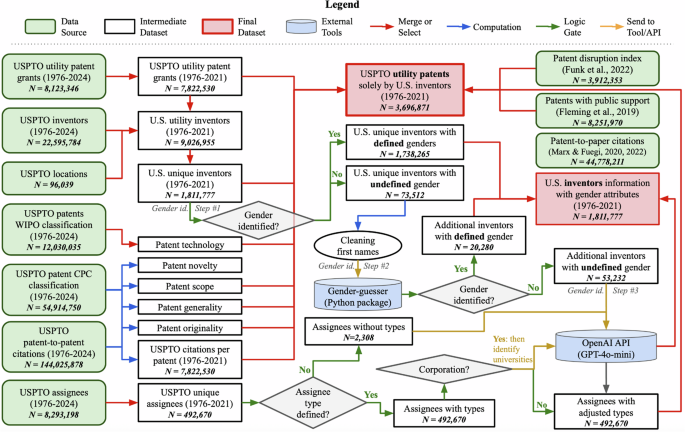

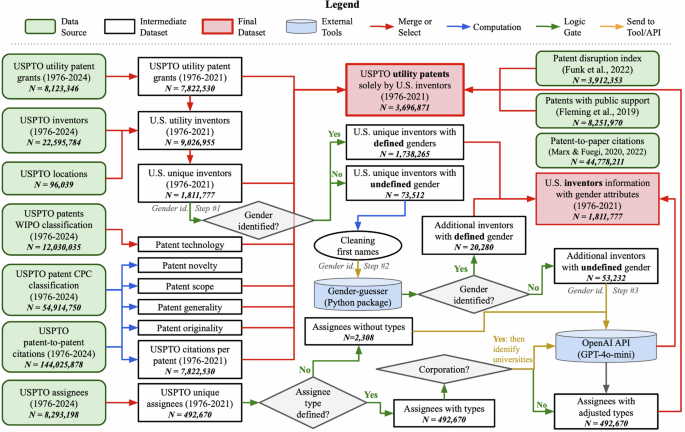

We collected knowledge on granted patents, inventors, assignees, areas, patent-to-patent citations, and expertise classifications from the PatentsViewFootnote 2 open knowledge platform (an initiative supported by the USPTO) in December 2024 (Toole et al., 2021). The course of of information assortment, cleansing, merging, and remaining development is illustrated in the flowchart in Fig. 1.

There are three sorts of patents granted in the United States: utility patents, design patents, and plant patents. Among these, utility patents, also called “patents for invention,” are the commonest and are broadly used in analysis as a proxy for general creative exercise in the U.S. (Griliches, 1990; Sampat, 2018; Seymore, 2013; Wang and Lobo, 2024; Youn et al., 2015).Footnote 3 Accordingly, we focus solely on utility patents for this examine. Also, the dataset consists of two sorts of expertise classifications. The first is the Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) system. The second is the sector and subject classification scheme developed by the WIPO.Footnote 4

The preliminary dataset consists of all utility patents filed between 1976 and September 30, 2024.Footnote 5 For our fundamental analyses, we chosen utility patents filed from 1976 by means of 2021. This subset consists of 7,822,530 granted utility patents, 20,228,153 inventor-patent situations, and three,834,487 distinctive inventors. Utility patents filed after 2021 are used solely to compute forward-looking metrics reminiscent of citations, which require a number of years of information accumulation post-grant.

The USPTO routinely receives purposes from overseas inventors (WIPO, 2021). Because this examine focuses on U.S.-based inventors, we additional restricted our dataset to 4,052,122 patents (51.8%) that had been invented solely by U.S. inventors, excluding patents involving any non-U.S. inventors.Footnote 6 This choice was made attainable by the inclusion of inventor nation data in the dataset; we retained solely these inventors whose nation designation was listed as “US.” Footnote 7

Of the three,834,487 distinct inventors in the total dataset, 1,856,323 (48.4%) are situated in the United States. Among them, 1,811,777 contributed to patents created solely by U.S. inventors, ensuing in 3,753,689 utility patents. This quantity was additional lowered to three,696,871 in our remaining dataset (highlighted by the crimson field in the higher center of Fig. 1) after excluding patents involving inventors with unknown or lacking gender data. This exclusion affected roughly 1.5% of the info, a proportion thought of acceptable given the scope of our examine.

To complement our analyses with data not offered by the USPTO, we included three further datasets:

-

a patent-to-paper quotation dataset (Marx, 2024; Marx and Fuegi, 2020, 2022), which hyperlinks U.S. patents to scientific publications listed in educational databases;

-

a dataset figuring out patents that depend on public funding (Fleming et al., 2019a, b); and

-

a dataset containing the disruption index for U.S. patents (Funk et al., 2022; Park et al., 2023).

The procedures for merging and processing these datasets are detailed in Fig. 1.

Gender attributes

Identifying inventors genders

We employed a three-step method to determine the gender of every inventor. This course of builds upon the pre-generated gender codes developed by Toole et al. (2019), supplemented by an AI-assisted technique, as described in this part.Footnote 8

Step #1: Pre-Generated Gender Code Using Name Databases

Because the USPTO doesn’t gather gender data in the course of the patent submitting course of, we depend on a pre-processed dataset developed by Toole et al. (2019), which makes use of probabilistic name-gender matching throughout two massive databases: (1) IBM’s Global Name Recognition (GNR) system and (2) WIPO’s Worldwide Gender-Name Dictionary (WGND). The technique applies a multi-step classification process based mostly on first-name chances and inferred country-of-origin data. Full particulars are offered in Appendix A.

In our dataset, this baseline technique efficiently assigned a gender to 1,738,265 of the 1,811,777 (95.9%) distinct U.S.-based inventors. Among these recognized, 1,509,486 (86.8%) had been labeled as male and 228,779 (13.2%) as feminine. The remaining 73,512 inventors both obtained an undefined label or had been lacking gender knowledge fully.

Step #2: Gender-Guesser Python Package

To deal with the 73,512 inventors with undefined gender data, we carried out two further steps. The first concerned utilizing the GENDER-GUESSER (Pérez, 2016), a Python package deal for gender inference based mostly on first names. This package deal attracts on knowledge from the “gender” program developed by Jörg Michael, which comprises gender data for about 40,000 first names throughout a number of languages and cultures (Gecko, 2009).

The package deal produces one in all six attainable outputs for every identify: male, mostly_male, feminine, mostly_female, andy (androgynous),Footnote 9 and unknown.Footnote 10 For the needs of this examine, we grouped male and mostly_male right into a single “male” class, and feminine and mostly_female right into a single “female” class. Names labeled as andy or unknown had been grouped into an “undefined” class. Applying this technique to the 73,512 gender-undefined inventors, we had been in a position to classify 15,624 as male and 4656 as feminine. The remaining 53,232 names remained undefined.

Step #3: LLM-Assisted Gender Classification

For the remaining 53,232 inventors whose gender couldn’t be recognized utilizing the earlier two steps, we employed a big language mannequin (LLM) to deduce gender. LLMs are a type of generative synthetic intelligence (GenAI) able to contextual textual content evaluation, reasoning, and content material era. In current social science analysis, LLMs have been more and more adopted for duties reminiscent of knowledge annotation, textual content era, data extraction, and evaluation, starting from sentiment evaluation (Miah et al., 2024), identification of political affiliations in social media posts (Törnberg, 2024), simulation of social conduct (Kim et al., 2025; Manning et al., 2024), and occupational process evaluation (Eloundou et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2025). While issues about transparency and replicability in utilizing LLMs for analysis persist (Lin and Zhang, 2025), we argue that gender inference from names is a very appropriate use case for LLMs, given their coaching on huge textual corpora that embrace culturally contextualized names.

For this process, we used GPT-4o-mini,Footnote 11 a cheap LLM developed by OpenAI, accessed through API. Prior to deployment, we engaged in iterative immediate engineering utilizing randomly sampled names in OpenAI’s Playground atmosphere.Footnote 12 To improve the mannequin’s contextual understanding, we constructed a dataset that included every inventor’s full identify,Footnote 13 location (metropolis, county, state, if obtainable), patent titles, assignee data (together with organizational identify and placement), and different related metadata related to their patent filings.

In our remaining immediate (see Appendix B), we instructed GPT-4o-mini to deduce the inventor’s gender utilizing all contextual data offered. The mannequin was requested to return JSON objects together with gender code—“M” for male, “F” for feminine, and “U” for undefined, together with a short rationalization and a confidence rating starting from 0.0 to 1.0. For instance, for the primary identify “Michael,” GPT-4o-mini responded: “Michael is a common male name” with a confidence rating of 0.9. For the identify Cuiyu Zhang, it responded: “Cuiyu Zhang is likely female based on the name’s structure, which is more common for female names in Chinese culture,” with a confidence rating of 0.7.

To consider the validity of this LLM-assisted method, we carried out a handbook validation utilizing 100 randomly-selected names for which gender had already been assigned by the USPTO (Toole et al., 2019) (Step #1). These names are thought of high-confidence circumstances, because the USPTO method is extra more likely to classify names with sturdy gender associations. We queried the gender of those 100 names utilizing our LLM-assisted technique and noticed a 94% settlement between GPT-4o-mini and the USPTO-assigned gender codes.Footnote 14 Therefore, we concluded that GPT-4o-mini, when used with our immediate and contextual knowledge, presents a degree of accuracy corresponding to the USPTO technique, demonstrating that the LLM-assisted method can, to an affordable diploma of accuracy, infer gender based mostly on inventor names and accompanying metadata.

Applying this method to the remaining 53,232 inventors, GPT-4o-mini initially labeled 33,940 as male (63.7%), 3470 as feminine (6.5%), and 15,822 (29.7%) as undefined. Given that many names are genuinely gender-neutral or culturally ambiguous, and recognizing the impossibility of good classification, our purpose was to not label each inventor however to take action with affordable confidence. To that finish, we retained solely these gender inferences with a confidence rating of 0.7 or larger, and assigned all others to the “undefined” class (“U”).

After this filtering step, the revised gender composition of the 53,232 previously unclassified inventors was as follows: 33,432 male (62.8%), 3425 female (6.4%), and 16,375 undefined (30.7%). A detailed breakdown of the number of inventors identified at each step is provided in Table 1.

Gender characteristics at the patent level

To enable patent-level analyses, we aggregated inventor gender information to the level of individual patents. We first removed 56,818 patents that included at least one inventor with an undefined gender, as the gender composition of these teams could not be accurately determined. These gender-unidentifiable patents represent only 1.5% of the entire dataset, a level of missingness that is widely considered acceptable in quantitative research. While this missingness is not completely random, it is attributable to systematic limitations in gender identification tools and does not pose a significant risk of bias to our analysis.Footnote 15

For the remaining 3,696,871 patents, we assigned the following three sets of gender-related attributes:

-

To study whether or not the presence of girls on a group influences invention traits, we created a binary variable, “with_women,” which takes the worth 1 if a minimum of one inventor is feminine, and 0 in any other case.

-

To examine gender collaboration patterns, we constructed a categorical variable, “gender_collab_type,” indicating the gender composition of the inventor group. This variable takes one in all three values: all-women group, all-men group, or mixed-gender group.

-

We additionally counted the variety of female and male inventors on every patent. If no feminine inventors had been current, the rely of feminine inventors was set to 0.

Assignee sorts

Identifying organizational assignee sorts

An assignee refers back to the particular person or group that holds the authorized possession rights to a patent. To examine variations in gender composition and disparities throughout organizational sorts, we labeled organizational assignees into three classes: authorities, universities, and personal corporations.

We started with 8,293,198 patent-assignee pairs (see Fig. 1), involving 492,670 distinctive assignees. From this pool, we chosen 216,149 distinctive assignees related to patents granted between 1976 and 2021 that had been invented solely by U.S.-based inventors.Footnote 16

To classify these assignee organizations, we used a multi-step course of combining structured knowledge from the PatentsView dataset with an LLM help. First, we utilized pre-assigned assignee sort codes to group entities into firms, governments, and people. Next, for assignees and not using a legitimate sort code, we utilized GPT-4o-mini to categorise organizations based mostly on their identify, patenting exercise, and geographic data. Finally, as a result of the USPTO usually classifies universities underneath the broader class of firms, we carried out an extra LLM-assisted step to determine universities inside this group and distinguish them from personal corporations. The detailed classification process is offered in Appendix C.

After consolidating the outcomes from all three steps, our remaining classification consists of 924 (0.4%) authorities assignees, 2595 (1.2%) universities, 212,396 (98.3%) firms, 175 people, and 59 unidentifiable assignees.

Classifying patents by assignee sort

A single patent might have a number of assignees, probably spanning completely different assignee sorts. Since our evaluation focuses on whether or not patents owned by governments and universities differ from these owned by firms in phrases of gender composition and patent high quality, we prioritized figuring out authorities and college possession.

We first labeled a patent as government-owned if a minimum of one in all its assignees was recognized as a authorities entity. Among the remaining patents, we then labeled these with a minimum of one college assignee as university-owned. The relaxation had been labeled based mostly on their assignee sort: company, particular person, unidentified, or null (indicating lacking assignee data).

This course of resulted in 40,595 (1.1%) government-owned patents, 145,698 (3.9%) university-owned patents, 2,950,992 (79.8%) corporation-owned patents, 170 patents assigned to people, 61 unidentified patents, and 559,355 patents with null assignee data.Footnote 17

Ex-ante patent traits

To study variations in the traits of patents produced by inventor groups with various gender compositions, we compiled a set of broadly used patent indicators. These indicators are divided into two classes: (1) ex-ante patent traits, described in this part, which seize attributes recognized on the time of patent submitting or mirror the character of the data embedded in the patent; and (2) ex-post patent traits (Section “Ex-post patent characteristics”), which signify outcomes or impacts noticed after the patent has been granted.

Patent scope

Patent scope refers back to the breadth of technological domains an invention spans, sometimes measured by the variety of distinct classification codes assigned to a patent. Broader scope usually displays larger technological complexity and integration throughout a number of data areas, and has been related to elevated agency worth and innovation efficiency (Barbieri et al. 2020; Lerner, 1994; Novelli, 2015; Wang et al. 2024). Historical traits additionally recommend an increase in scope over time, particularly for the reason that mid-Twentieth century (Youn et al. 2015).

To measure patent scope, we use the Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) system adopted by the USPTO. Each patent is assigned a number of CPC codes, which signify the non-trivial technical elements disclosed in the invention (USPTO, 2015).Footnote 18 Following prior literature (Barbieri et al. 2020; Strumsky et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2024; Youn et al. 2015), we outline the technological scope of a patent because the variety of distinctive 4-digit CPC subclass codes it receives. Each subclass code corresponds to a definite technical fields.Footnote 19

While our fundamental focus is on 4-digit CPC codes, we additionally counted the variety of full-digit subgroup codes as a management variable to account for the extent of technical granularity.Footnote 20

To account for variation in group measurement, we additionally compute per-inventor scope by dividing the variety of 4-digit CPC codes by the variety of inventors listed on every patent.

Originality

To assess the variety of data sources included into an invention, we computed the originality index, a broadly adopted metric in patent research (Breitzman and Thomas, 2015a; Hall et al., 2001; Hasan et al., 2009; Jaffe and Trajtenberg, 2002; Squicciarini et al., 2013; Su, 2022). This index measures the extent to which a patent builds upon prior innovations from completely different technological fields, based mostly on its backward citations.

The originality rating for a given patent p, denoted as Op, is calculated as:

$${O}_{p}=1-mathop{sum }limits_{t=1}^{{N}_{p}}{s}_{pt}^{2}$$

(1)

the place spt represents the share of backward citations made by patent p that fall underneath CPC 4-digit code t, and Np is the variety of distinct 4-digit CPC codes amongst all cited patents. A better Op worth signifies that the cited prior artwork spans a broader vary of technical fields, suggesting larger originality. In distinction, if a patent cites solely prior work from a single subject, the originality rating Op equals zero.

Combinatorial novelty

Inventions are sometimes conceptualized as novel mixtures of present applied sciences (Arthur, 2009; Schumpeter, 1934; Wagner and Rosen, 2014; Youn et al., 2015). Although novelty is a proper requirement for patentability (35 U.S. Code § 102), its analysis by patent examiners is inherently subjective and context-dependent, making it tough to quantify systematically. To deal with this problem, researchers have developed empirical strategies to measure the novelty of data recombinations in patents and scientific publications, demonstrating their predictive worth for future influence (Kim et al., 2016; Mukherjee et al., 2016; Uzzi et al., 2013; Youn et al., 2015).

We undertake a classification-based technique developed by Strumsky and Lobo (2015) to evaluate the combinatorial novelty of patents. This method categorizes patents based on whether or not they introduce new technological elements (outlined utilizing full-digit CPC codes) and/or novel mixtures of these elements. The taxonomy consists of 4 classes: (1) Origination, the place all assigned elements are new to the patent system; (2) Novel Combination, which mixes new and present elements; (3) Combination, which makes use of solely beforehand recognized elements however kinds new pairwise mixtures; and (4) Refinement, in which each the elements and their mixtures have appeared in prior patents.

Strumsky and Lobo (2015) reported a gradual decline in Origination and Novel Combination patents, with every comprising lower than 1% of all patents after 1990. The majority of novel exercise in current many years arises from new mixtures of present elements, fairly than from fully new applied sciences. To mirror this actuality and keep away from extremely imbalanced classes, many research have adopted a binary definition of novelty, classifying patents as novel in the event that they introduce a minimum of one new pairwise mixture of elements, no matter whether or not the elements themselves are new (Verhoeven et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2024). Under this method, the primary three classes outlined by Strumsky and Lobo (2015)—Origination, Novel Combination, and Combination—are grouped collectively as “novel,” whereas solely the Refinement class is taken into account “non-novel.”

Following this logic, we outline a binary indicator of combinatorial novelty, assigning a price of 1 to patents that introduce new elements or new mixtures (i.e., non-Refinement patents), and 0 to people who introduce neither (i.e., Refinement patents). Using this classification, we recognized 1,806,610 patents (48.9%) in our dataset as novel, and 1,890,261 patents (51.1%) as Refinements.Footnote 21

Patents counting on public help

To study how inventors of various genders depend on publicly funded analysis, we utilized a dataset of government-supported patents compiled by Fleming et al. (2019b).Footnote 22 This dataset classifies a patent as counting on public analysis if it meets a minimum of one of many following standards: (1) the patent is owned by the federal government, (2) the patent explicitly acknowledges authorities funding, or (3) the patent cites a previous patent or publication that satisfies both of the primary two standards or is authored by a person affiliated with a U.S. authorities establishment (Fleming et al., 2019a).

The first two sorts are thought of direct public help, as they mirror formal and monetary backing from authorities sources. The third sort captures oblique public help, representing the data spillover results of publicly funded analysis. In our evaluation, we group each direct and oblique help underneath a single class (Relying on Public Support) to seize any reliance on data created with public funding, help, or useful resource.

Using this classification, we recognized 654,878 patents (17.7%) as counting on public help, whereas the remaining 82.3% didn’t present any such dependence.

Patents counting on science

Scientific analysis and discovery have lengthy served as key sources of inspiration for innovations and technological development. One frequent technique of mapping the stream of data from science to expertise is thru analyzing patent citations to scientific publications (Jaffe et al., 1993, 2000; Meyer, 2000; Narin and Noma, 1985; Tussen et al., 2000).

In this examine, we used an open-access dataset developed by Marx and Fuegi (2020), which hyperlinks patents granted worldwide to scientific articles revealed for the reason that 1800s (Marx and Fuegi, 2020, 2022). This dataset identifies roughly 22 million patent citations to science (PCS), constructed by means of high-precision matching of the non-patent literature (NPL) part in patent paperwork to entries in bibliographic databases reminiscent of MEDLINE, Web of Science, and CrossRef. The authors employed a mix of rule-based parsing, metadata alignment, and handbook validation to make sure accuracy and world protection.

Using this dataset, we study whether or not the gender composition of inventor groups influences the extent to which patents depend on scientific data. We deal with two key measures: (1) the variety of scientific publications cited in a patent, which displays the general diploma of reliance on science; and (2) the variety of citations per inventor, which adjusts for group measurement and approximates individual-level engagement with scientific analysis.

Ex-post patent traits

Ex-post patent traits are attributes that grow to be observable solely after a patent is granted, usually reflecting its technological or business influence. In this examine, we use three broadly adopted ex-post measures to evaluate the realized affect of patents throughout completely different inventor group gender compositions: ahead citations, the generality index, and the disruption index. These seize, respectively, the extent of a patent’s affect on subsequent innovations, the breadth of that affect throughout fields, and whether or not the patent disrupts or consolidates present quotation constructions.

Forward citations

Forward citations made by subsequent patents to a focal patent are a broadly used proxy for a patent’s technological influence and data diffusion (Barbieri et al., 2020; Fleming and Sorenson, 2004; Hall et al., 2001; Trajtenberg and Jaffe, 2002). Higher ahead quotation counts usually sign larger affect on future improvements and broader spillover results (Jaffe et al., 2000).

In this examine, we seize ahead quotation influence utilizing two measures: (1) a rely variable representing the variety of ahead citations a patent receives inside 5 years of its grant date, and (2) a binary variable indicating whether or not the patent is a “top-cited” or “hit” patent, outlined as being in the highest 10% of ahead citations amongst all patents granted in the identical 12 months. The inclusion of the binary variable accounts for the extremely skewed and probably uneven distribution of citations throughout patents, which can obscure variations between inventor groups of various gender compositions. This method follows prior research by Uzzi et al. (2013) and Mukherjee et al. (2016).

Generality

The generality index captures the extent to which a patent influences a broad vary of technological domains (Barbieri et al., 2020; Trajtenberg and Jaffe, 2002). A better generality rating signifies {that a} patent is cited by subsequent patents from a greater variety of fields, reflecting its cross-domain applicability.

In this examine, we undertake a modified model of the generality index proposed by Squicciarini et al. (2013), calculated over a five-year quotation window. Let Yp signify the set of patents that cite focal patent p inside 5 years of its grant date. For every citing patent y ∈ Yp, let My be the set of full-digit CPC codes, and Ny be the corresponding 4-digit CPC codes.

The union of all 4-digit CPC codes throughout citing patents is denoted as:

$${{mathbb{N}}}_{p}=bigcup _{yin {Y}_{p}}{N}_{y}$$

(2)

The generality index Gp for patent p is computed as:

$${G}_{p}=1-sum _{nin {{mathbb{N}}}_{p}}{left(frac{1}{| {Y}_{p}| }sum _{yin {Y}_{p}}{beta }_{yn}proper)}^{2}$$

(3)

the place βyn represents the share of full-digit CPC codes in y that fall underneath the 4-digit code n, calculated as:

$${beta }_{yn}=frac{{T}_{yn}}{| {M}_{y}| }$$

(4)

Here, Tyn is the variety of full-digit codes in y that map to a 4-digit code n, and ∣My∣ is the entire variety of full-digit codes in y.

This index ranges from 0 to 1, with larger values indicating that the citing patents span a extra numerous set of technological lessons, suggesting broader generality of the cited patent.

Disruption

While ahead citations measure the quantity of a patent’s subsequent affect, and generality captures the breadth of its influence throughout fields, neither metric displays how a patent impacts the route of future innovation. Specifically, they don’t point out whether or not a patent reinforces present technological trajectories or breaks away from them to determine new paths. Therefore, we incorporate the Consolidating-or-Disruptive index (CD index), a measure that captures how a lot a patent destabilizes the prevailing data construction by redirecting the stream of citations (Funk and Owen-Smith, 2017).

The CD index ranges from −1 to 1, with optimistic values indicating larger disruption. A patent is taken into account disruptive if future patents are inclined to cite it however not its predecessors, suggesting that it redirects the stream of data and introduces a novel technological route. In distinction, a consolidating patent is one that’s regularly co-cited with its prior artwork, reinforcing present data constructions and increasing established technological trajectories with out initiating a brand new path (Park et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2019).

Formally, the CD index at time t is computed as:

$$C{D}_{t}=frac{1}{{n}_{t}}mathop{sum }limits_{i=1}^{{n}_{t}}(-2{f}_{i}{b}_{i}+{f}_{i})$$

(5)

the place fi signifies whether or not a later patent i cites the focal patent, bi signifies whether or not it cites one of many focal patent’s predecessors, and nt is the variety of patents citing both the focal patent or its predecessors as of time t (Park et al., 2023).

We use a pre-computed dataset of CD indices for patents granted between 1976 and 2010 (Funk et al., 2022), which incorporates three time horizons: five-year, ten-year, and cumulative as of 2017.Footnote 23 To keep consistency with our ahead quotation and generality analyses, we deal with the five-year CD index (CD5).

In addition to utilizing the continual CD index, we assemble a binary “disruption hit” or “top disruptive” indicator that equals 1 if a patent’s CD5 rating falls throughout the prime 10% of its grant-year cohort, and 0 in any other case. This binary measure captures the distributional skewness of disruption and permits us to look at whether or not sure inventor group traits are related to an elevated chance of manufacturing extremely disruptive patents (Mukherjee et al., 2016).

Descriptive statistics for variables mentioned in Section “Data” are introduced in Table 2.