Justice Anthony Kennedy thought-about quitting the Supreme Court over abortion.

Kennedy, who served from 1988 to 2018, makes the revelation in a new guide as he explains how he balanced his Catholic faith and finally forged the deciding vote in 1992 that saved abortion rights for the following three a long time.

His writings and a recent book by Justice Amy Coney Barrett, a conservative Catholic who supplied the important thing vote in 2022 to finish a constitutional proper to acquire an abortion, present a uncommon window into private conflicts relating to faith and the regulation.

Catholics have more and more dominated the excessive court docket and prompted debate over how the justices’ faith influences their choices. The books arrive at a bigger second in America as Christian nationalism appears to be growing and debate over faith and politics has escalated.

“Because of my ever-constant belief that life must be protected from the moment of conception,” Kennedy wrote in his guide to be revealed on October 14, “I struggled with the idea that the Constitution should allow some choice to end a pregnancy.”

Kennedy says he was notably torn throughout the 1992 case Planned Parenthood v. Casey, when the justices have been deciding whether or not to affirm or reverse Roe v. Wade, the milestone that made abortion authorized nationwide.

“The struggle led me to wonder whether it would be wrong for me, morally, to stay on the Court if doing so would require me to rule under the law that women have the right to end a pregnancy in its early, pre-viability stage,” Kennedy writes. “My conclusion, reached in private and without discussion with others, was to stay on the Court.”

Today’s Supreme Court, managed by justices extra solidly conservative than Kennedy, has permitted better mixing of church and state, by a coach’s prayers at public school football games, authorities financing of sectarian education, and non secular monuments on government land.

The court docket has additionally moved rightward on social coverage points imbued with a non secular dimension, corresponding to reproductive rights and LGBTQ rights. The latter will quickly be examined once more, when the court docket in October hears a dispute over state efforts to ban well being care professionals from participating in “conversion therapy” with minors to alter their sexual orientation or gender id.

The justices can even take up a problem to state bans on trans athletes in class sports activities. (In a case earlier this yr, because the right-wing majority let states ban puberty blockers and hormone remedy for teens looking for to transition to match their gender id, Barrett steered she opposed granting transgender id the identical anti-discriminatory protections that the Constitution supplies based mostly on race and intercourse.)

University of Virginia regulation professor Douglas Laycock, who has lengthy centered on instances involving the First Amendment ensures of faith, says folks naturally marvel how the justices’ faith performs into their choices.

“There’s lots of speculation about how religion is influencing them,” he mentioned. “It’s always useful to know how they approach cases.”

Yet Laycock cautions that explanations could also be shaded by a sort of wishful pondering. “These are people resolving what appear to be deep, internal conflicts,” he mentioned.

Both Kennedy and Barrett, appointed in 2020 and nonetheless sitting, have been pivotal justices. Their new books and respective data show how a lot the court docket has modified over time on controversies that contact on faith.

Kennedy ended up casting the important thing vote to reaffirm the 1973 Roe v. Wade case, concluding the Constitution protected a proper to abortion earlier than viability, that’s, the purpose at which a fetus can survive outdoors the womb. That was the regulation till 2022, when Barrett went in the wrong way and supplied the fifth vote to strike down Roe.

In “Listening to the Law,” revealed in September, Barrett defended her vote in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Center. While she writes about her Catholicism within the context of the demise penalty, she avoids any point out of her faith as she defined why she rejected Roe.

Kennedy writes in his guide that he disliked being described because the court docket’s “swing vote,” however the centrist conservative continuously made the distinction in necessary instances. An appointee of President Ronald Reagan, Kennedy navigated between the right- and left-wing blocs, over time aligning extra with the left on social points.

“My colleagues knew, too, that religious and traditional family values had led me to feel some personal conflict over these matters,” Kennedy wrote as he mentioned his votes on homosexual rights in “Life, Law & Liberty.” “Because my colleagues knew of these tensions, and the cases looked as if they would be closely divided, the opinions were assigned to me.”

On homosexual rights, Kennedy clashed most with fellow Catholic Antonin Scalia, with whom he served for almost his entire time, till Scalia’s demise in 2016. Kennedy reveals in his guide that after the court docket’s 2015 opinion declaring a proper to same-sex marriage, Scalia hardly ever spoke to him or attended the justices’ lunches.

Such variations between Kennedy and Scalia supply a reminder that the court docket’s conservative Catholics cowl a vary. There was a good better distinction with their Catholic colleague William Brennan, an unyielding liberal. Brennan sat from 1956-1990 and died in 1997.

In 1973 when Roe was determined, Brennan was the one Catholic on the Supreme Court. “I wouldn’t under any circumstances condone an abortion in my private life,” he mentioned, in line with a 2010 Brennan biography by Seth Stern and Stephen Wermiel. “But that has nothing to do with whether or not those who have different views are entitled to have them and are entitled to be protected in their exercise of them. That’s my job in applying and interpreting the Constitution.”

There are actually six justices on the precise wing who’re both practising Catholics (Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Brett Kavanaugh and Barrett) or have been raised Catholic (Neil Gorsuch, now an Episcopalian). A seventh Catholic justice, Sonia Sotomayor, firmly resides on the liberal wing.

Among these present Catholics, Alito has been most outspoken in his views. He has headlined Catholic-sponsored occasions and repeatedly contends that faith is beneath siege.

Last yr in a speech to graduates of Franciscan University of Steubenville in Ohio, he mentioned, “Freedom of religion is also imperiled. When you venture into the world you may well find yourself in a job or a community or a social setting when you will be pressured to endorse ideas you don’t believe, or to abandon core beliefs. It will be up to you to stand firm.”

Barrett says in her guide that she was stunned her Catholicism was raised in a 2017 listening to earlier than the Senate Judiciary Committee, when President Donald Trump first nominated her for a seat on a Chicago-based US appellate court docket.

Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein referred to the writings of Barrett, who was then a University of Notre Dame regulation professor. “The conclusion one draws,” Feinstein mentioned, “is that the dogma lives loudly within you. And that’s of concern when you come to big issues that large numbers of people have fought for, for years in this country.”

Some Republican senators mentioned Barrett had been wrongly confronted with a “religious test,” and even Feinstein’s Democratic colleagues thought she had awkwardly raised the difficulty. (For her 2020 Supreme Court listening to, Democratic senators largely prevented questions involving faith or her affiliation with the Christian group People of Praise.)

In her guide, Barrett writes, with out naming Feinstein, who has since died, “Some suggest that people of faith have a particularly difficult time following the law rather than their moral views. (I faced that criticism as a Catholic, most sharply when the Senate Judiciary Committee conducted a hearing to consider my nomination to the Seventh Circuit.) I’m not sure why.”

She then provides, “Fortunately for the health of our country, people of faith are not the only Americans with firm convictions about right and wrong. Nonreligious judges also have deeply held moral commitments, which means that they too face conflicts between those commitments and the demands of the law. A secular humanist who passionately believes that access to abortion is a moral imperative must set aside her views, no less than the judge whose faith informs a moral objection to abortion.”

Barrett referred to her private opposition to capital punishment and her votes to uphold the demise penalty.

“For me, death penalty cases drive home the collision between the law and my personal beliefs,” she writes. “Long before I was a judge – before I was even a member of the bar – I co-authored an academic article expressing a moral objection to capital punishment.”

She then famous that she forged a vote in 2022 with the bulk to reinstate a death sentence for Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, convicted within the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing.

“Swearing to apply the law faithfully means deciding each case based on my best judgment about what the law is,” she writes. “If I decide a case based on my judgment about what the law should be, I’m cheating.”

Both Barrett and Kennedy clarify that their Catholicism is central to their private identities. Kennedy ended up aligning much less with church teachings.

At the time he was conflicted over his Catholicism and abortion rights, Kennedy concluded: “To resign in effect would have been to say that the judicial oath to protect constitutional rights is not binding in difficult or controversial cases. And as a practical matter, in those times, it was possible that my successor would be less concerned about protecting the unborn.”

Scalia and homosexual rights

Kennedy means that his choices favoring homosexual rights got here with much less anguish. But that is the place he fought with Scalia, a fellow Catholic of the identical era (each have been born in 1936) and equally appointed by Reagan.

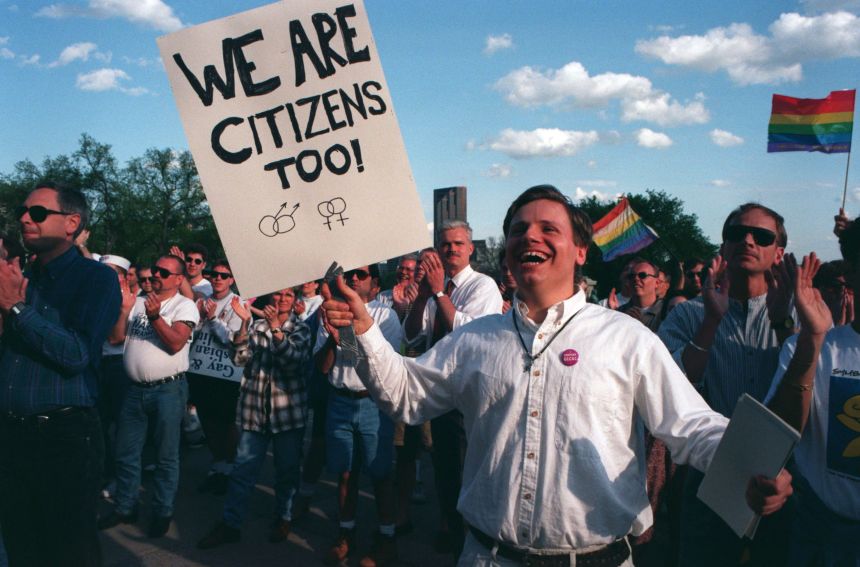

When Kennedy authored his first main opinion favoring LGBTQ pursuits, in a 1996 case that struck down a Colorado state ballot initiative that prevented localities from defending homosexual and lesbian rights, he was startled by Scalia’s dissenting views.

The Kennedy majority had mentioned the voter initiative violated the constitutional assure of equal safety and had appeared “inexplicable by anything but animus.”

Scalia countered in his dissenting opinion, “This Court has no business imposing upon all Americans the resolution favored by the elite class from which Members of this institution are selected, pronouncing that ‘animosity’ toward homosexuality is evil.”

In his new guide, Kennedy writes, “The vehemence of the dissent – and of Justice Scalia’s dissents in later cases on the subject – truly surprised and disappointed me and a number of my colleagues.”

About twenty years after that ruling in Romer v. Evans, their relations worsened when Kennedy crafted the 2015 Obergefell v. Hodges resolution permitting same-sex marriage nationwide and Scalia penned a harsh dissent.

“After Obergefell was announced in June and our new session began in October, Nino rarely came to lunch with us or stopped by to chat,” Kennedy writes, including that his kids have been upset by the dissent’s “rare personal attack” on Kennedy.

Then in early February 2016, Scalia visited Kennedy in his chambers. Referring to Scalia by his nickname, Kennedy wrote, “Nino said he had come to regret deeply the tone of his Obergefell dissent and its personal references. He apologized for being intemperate. We both smiled, and the matter was resolved.”

Scalia was about to depart for a searching journey in Texas.

Kennedy recalled him saying, “Tony, this is my last long trip.” Scalia died a little over a week later whereas on that journey.

“Those parting words were the last we ever spoke to each other.”