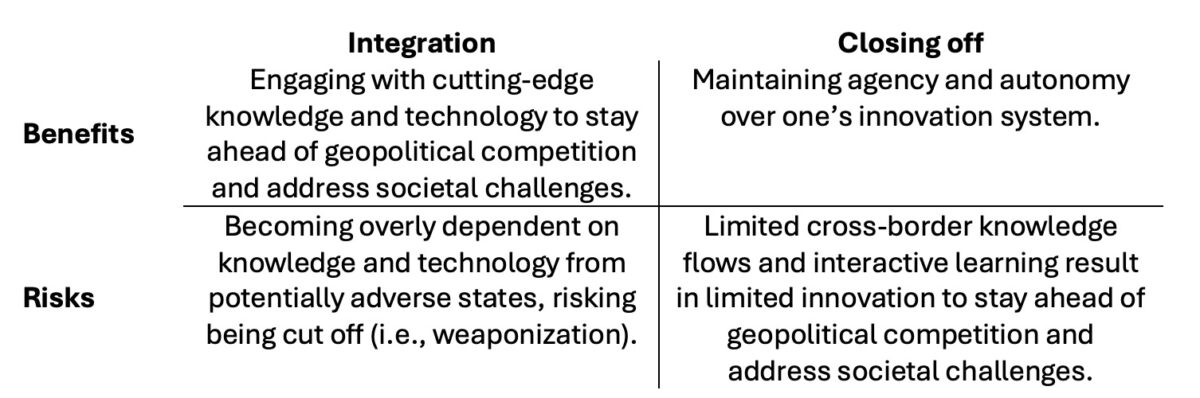

Over the previous few years, geopolitical competitors has been growing, and this competitors has grow to be largely technology-based (OECD 2023). In an innovation system that’s extremely globally intertwined, this raises a fancy dilemma for governments (see Table 1). On the one hand, maximally integrating into these techniques enhances innovation and subsequently competitiveness and the power to handle societal challenges equivalent to local weather change, but it surely will increase dangers of weaponized interdependence when changing into too depending on adversarial states. On the opposite hand, closing off and securitizing innovation grants extra autonomy, however dangers operating behind in worldwide technology-based competitors when not having the ability to reap the advantages of open data flows, interactions, and studying about essentially the most superior applied sciences (Tan et al. 2025; Edler et al. 2023; Lee et al. 2024).

This query touches straight on the educational fields of International Relations (IR) and research. It is subsequently more and more being studied by associated educational communities in Europe, such because the Eu-SPRI discussion board (innovation coverage) and EISA-PEC (IR). As a PhD Candidate in innovation coverage with a background in IR, I visited each their conferences this summer season to see how the 2 communities method this query and, extra importantly, what they’ll study from one another.

The European Forum for Studies of Policies for Research and Innovation (Eu-SPRI Forum) represents a analysis discipline evolving for the reason that Sixties on the encounter of economics, political science, sociology, Science and Technology Studies (STS), enterprise administration, geography, and historical past. Historically, the sector has targeted on two rationales or ‘frames’ for partaking in innovation coverage, the primary being addressing market failures. Examples are uncertainty about outcomes and brief funding horizons, which result in a continual undersupply of personal R&D funding, with corporations tending to favor simply relevant, incremental innovation over basic analysis with better potential for radical breakthroughs. After the Second World War, through the early Cold War, Western governments began institutionalizing supply-side innovation insurance policies to repair such market failures. Popular devices are R&D subsidies or tax credit for knowledge-intensive corporations, which stay the cornerstone of many current innovation insurance policies, additionally, for instance, within the Draghi report on the European Union’s (EU) competitiveness. Towards the top of the Cold War, the main focus expanded to a second body: creating aggressive nationwide innovation techniques in a globalizing world by addressing system failures, equivalent to weak university-industry hyperlinks, which impede the commercialization of analysis. Various fashions emerged to evaluate how interactions between totally different actors form innovation and to establish gaps governments can tackle, together with the university-industry-government ‘Triple Helix’ mannequin (Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff 2000), (technological) innovation techniques (TIS) (Hekkert et al. 2007), and entrepreneurial ecosystems (Stam 2015). Staying within the Netherlands, an instance may be present in Brainport Eindhoven, grouping Eindhoven University of Technology with high-tech corporations like ASML, at the moment on the heart of global technology-based competition.

Since the mid-2010s, the sector has expanded its focus to a 3rd body, not solely learning learn how to facilitate R&D investments and innovation techniques, but additionally learn how to actively create and help markets for promising improvements, steering demand in direction of addressing societal challenges equivalent to local weather change and healthcare in instances of an growing older inhabitants (Schot and Steinmueller 2018; Weber and Rohracher 2012; Mazzucato 2016). For occasion, governments can act as lead clients for inexperienced improvements by incorporating such innovations in their public procurements or utilizing rules and requirements to lift the bar and direct improvements in direction of particular coverage targets (Edler and Georghiou 2007). These three frames for innovation coverage, till lately, all targeted on a scenario displayed by the higher left quadrant of Table 1, i.e., reaping the advantages of worldwide data trade and studying. Recent geopolitical developments, equivalent to a extra assertive China on the worldwide stage and growing US isolationism, led to elevated consideration within the EU for the position innovation coverage can play to remain forward in such competitors, in addition to the dangers of worldwide technology-based competitors, as displayed within the different quadrants in Table 1. Consequently, Edler et al. (2023) urged a fourth innovation coverage body within the form of know-how sovereignty, i.e., the capability of a state to develop or supply important applied sciences for welfare, competitiveness, and autonomy, with out one-sided dependencies.

At Eu-SPRI 2025, three of the thirty parallel sections explicitly targeted on security-related points. One part targeted totally on a conceptual degree on how requires extra autonomy have an effect on the capability of governments to boost innovation and tackle different societal challenges. One presentation outlined, for instance, how European nations’ pledge to extend their protection budgets to five% of GDP may be framed as a standard supply-side ‘technology push’ coverage primarily based on R&D subsidies (body 1). Without utilizing components of this finances to actively create markets for European improvements (frames 3 and 4), for instance, through the use of (pre-commercial) public procurement as a instrument to stimulate protection innovation, it merely deepens dependencies on the US navy {industry}. It additionally decreases budgets for different innovation coverage targets, equivalent to sustainability transitions. A model of the presentation may be discovered on the LSE European Politics and Policy blog (Frenken 2025). Sections on particular analysis and innovation subjects exhibited extra in-depth, empirical work. For instance, a piece on analysis safety (body 2) and dual-use innovation examined how establishments and governments navigate the stress between scientific openness and collaboration on the one hand, and safety dangers and uneven responses between and inside analysis techniques on the opposite. A synthesis of this part’s conclusions may be discovered on this blog of the University of Manchester (James and Flanagan 2025).

Looking again at Eu-SPRI and relating it to the dilemma offered in Table 1, I figured that the present innovation coverage literature primarily focuses on the stability between the higher left and the underside proper quadrant. More particularly, on the query of learn how to make interactions safer, and the results of decreased interactions on the capability to innovate. An instance is the rising consideration on learn how to safeguard important applied sciences (high proper quadrant), grouped across the idea of technological sovereignty. Overall, current research are primarily involved with how geopolitics have an effect on present innovation practices and targets, and much less with offensive practices of weaponized interdependencies (backside left quadrant), or the position of innovation in creating aggressive benefits in geopolitical competitors. For these subjects, one has to show to IR.

The Pan-European Conference on International Relations (PEC) is the primary annual occasion of the European International Studies Association (EISA). Work offered at EISA-PEC tends to give attention to conceptual relatively than methodological energy because of the events-driven nature of the self-discipline. A keynote panelist described that, in instances of relative peace and multilateral cooperation, the self-discipline turns liberal and pro-interdependencies, whereas in instances of elevated world competitors and pressure, IR students shortly go away their former love for liberal theories, and realists advocating for financial autonomy prevail. Resonating with customary work on scientific revolutions (Kuhn 2012), as conceptual settlement is missing, there may be restricted room for empirical and methodological depth.

At EISA-PEC, 5 out of 34 particular parallel sections have been associated to know-how and innovation, subsequent to 23 standing sections on extra classical IR subjects (e.g., “Realist thought, theory, and analysis in IR”). Due to robust hyperlinks with the constructivist and qualitative research-oriented discipline of STS, a number of sections confirmed how know-how as a social-political assemble shapes energy and safety in worldwide relations, primarily on the particular person know-how degree. For instance, a section with researchers from the Intimacies of Remote Warfare challenge introduced collectively important views on the idea of “responsibility” within the context of algorithmic and distant warfare. Overall, nevertheless, much less consideration was devoted to the query of the place know-how really comes from and how governments can help promising improvements. Where this was executed, innovation was offered as a relatively linear course of, with out a lot consideration to the systemic nature of the innovation course of (body 2), or the fragile political means of mobilizing and steering demand (body 3), extensively studied within the innovation coverage literature.

One notable exception to this declare was an International Political Economy part on geopolitics and financial statecraft, organized by the Multi-layered governance in EUrope and beyond analysis group on the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. The part entailed high-quality qualitative and quantitative empirical work on financial statecraft and geoeconomics, i.e., how states deploy financial devices and leverage interdependencies to pursue international coverage targets, form energy relations, and handle worldwide competitors (Babić et al. 2024). In this group, devices are reframed as “market-creating”, “market-correcting”, “market-intervening”, and “market-directing” (Van Apeldoorn and De Graaff 2022) as an alternative of devices categorized by market, system, and demand-steering failures (Schot and Steinmueller 2018; Weber and Rohracher 2012). Unlike the innovation coverage literature, this group clearly distinguishes between such insurance policies’ nationwide and worldwide/geopolitical dimensions. For instance, Van Apeldoorn and De Graaff (2022) argue that by (partially) state-owned enterprises, Sovereign Wealth Funds, or worldwide funding by the federal government or supported home corporations, states can direct or management markets past their very own borders to pursue their very own international coverage targets. However, the coverage fields mentioned at EISA-PEC have been a lot broader than at Eu-SPRI, primarily specializing in industrial coverage, commerce, finance, and provide chains, with restricted consideration to innovation coverage. This leaves the query of the place innovation comes from and how geopolitics may improve or impede its emergence largely unresolved, which is problematic contemplating the remark that competitors is fiercest within the know-how area (OECD 2023).

Relating my insights from EISA-PEC to the dilemma in Table 1, I might argue that this European IR group is usually preoccupied with learn how to transfer away from the underside left quadrant (dangerous dependencies in a extremely intertwined world financial system), in direction of the higher proper quadrant (sustaining autonomy and energy in such an financial system). Studies additionally give attention to transferring to the higher left quadrant, however solely contemplate consideration as a way to remain forward in geopolitical competitors relatively than utilizing it to handle different societal challenges. Consequently, much less effort is dedicated to the prices of decreased data flows and cross-border studying (backside proper quadrant), particularly in gentle of different coverage targets which may obtain much less consideration and budgets because of elevated geopolitical tensions, equivalent to sustainability transitions.

Both fields give attention to totally different components of the technology-based worldwide competitors dilemma as offered in Table 1. Innovation research are primarily involved with how geopolitics and worldwide safety have an effect on present practices and targets, and much less with how innovation coverage additionally shapes geopolitics. Conversely, IR may be very properly conscious of innovation and know-how’s position in worldwide competitors, however solely to a restricted extent scrutinizes the place these capabilities come from and how geopolitical selections may have an effect on innovation coverage.

Combining insights from each fields may provide a extra holistic view of the dilemma offered within the intro. For instance, it might be attention-grabbing to have a look at how the technology-based worldwide competitors dilemma impacts the emergence of innovation inside complicated techniques, i.e., leading to an IPE perspective on the Triple Helix, entrepreneurial ecosystems, or TIS literature. Next to learning the advantages of open data flows and dangers of closing off, it might even be attention-grabbing to suppose extra concerning the geoeconomics and financial statecraft facet of innovation insurance policies. Following Van Apeldoorn and De Graaff (2022) within the IPE discipline, this might embrace research on, for instance, the meant or unintended international results of home innovation insurance policies.

Table 1. Overview of integration vs. closing-off dilemma for governments in instances of worldwide technology-based competitors (primarily based on Tan et al. 2025)

References

Babić, Milan, Nana de Graaff, Lukas Linsi, and Clara Weinhardt. 2024. “The Geoeconomic Turn in International Trade, Investment, and Technology.” Politics and Governance 12 (0). https://www.cogitatiopress.com/politicsandgovernance/article/view/9031.

Edler, Jakob, Knut Blind, Henning Kroll, and Torben Schubert. 2023. “Technology Sovereignty as an Emerging Frame for Innovation Policy. Defining Rationales, Ends and Means.” Research Policy 52 (6): 104765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2023.104765.

Edler, Jakob, and Luke Georghiou. 2007. “Public Procurement and Innovation—Resurrecting the Demand Side.” Research Policy 36 (7): 949–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2007.03.003.

Etzkowitz, Henry, and Loet Leydesdorff. 2000. “The Dynamics of Innovation: From National Systems and ‘Mode 2’ to a Triple Helix of University–Industry–Government Relations.” Research Policy 29 (2): 109–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(99)00055-4.

Frenken, Koen. 2025. “The New NATO Spending Target Will Hamper Europe’s Innovation Policy.” LSE EUROPP – European Politics and Policy. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2025/06/30/the-new-nato-defence-spending-target-will-hamper-europes-innovation-policy/.

Hekkert, M. P., R. A. A. Suurs, S. O. Negro, S. Kuhlmann, and R. E. H. M. Smits. 2007. “Functions of Innovation Systems: A New Approach for Analysing Technological Change.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 74 (4): 413–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2006.03.002.

James, Andrew, and Kieron Flanagan. 2025. “The Geopolitics of International Research Collaboration and the Impact of Research Security Concerns.” Research and Higher Education. Manchester Institute of Innovation Research Blog, January 6. https://blogs.manchester.ac.uk/mioir/2025/01/06/the-geopolitics-of-international-research-collaboration-and-the-impact-of-research-security-concerns/.

Kuhn, Thomas S. 2012. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions: fiftieth Anniversary Edition. Edited by Ian Hacking. University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/ebook/chicago/S/bo13179781.html.

Lee, Jeong-Dong, Hanbin Kim, Saerom Si, and Saangkeub Lee. 2024. “Techno-Nationalism to Collaborative Technology Sovereignty.” Science and Public Policy, August 23, scae046. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scae046.

Mazzucato, Mariana. 2016. “From Market Fixing to Market-Creating: A New Framework for Innovation Policy.” Industry and Innovation 23 (2): 140–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2016.1146124.

OECD. 2023. OECD Science, Technology and Innovation Outlook 2023: Enabling Transitions in Times of Disruption. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-and-technology/oecd-science-technology-and-innovation-outlook-2023_0b55736e-en.

Schot, Johan, and W. Edward Steinmueller. 2018. “Three Frames for Innovation Policy: R&D, Systems of Innovation and Transformative Change.” Research Policy 47 (9): 1554–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.08.011.

Stam, Erik. 2015. “Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Regional Policy: A Sympathetic Critique.” European Planning Studies 23 (9): 1759–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2015.1061484.

Tan, Yeling, Mark Dallas, Henry Farrell, and Abraham Newman. 2025. “Driven to Self-Reliance: Technological Interdependence and the Chinese Innovation Ecosystem.” International Studies Quarterly 69 (2): sqaf017. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqaf017.

Van Apeldoorn, Bastiaan, and Naná De Graaff. 2022. “The State in Global Capitalism before and after the Covid-19 Crisis.” Contemporary Politics 28 (3): 306–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2021.2022337.

Weber, Ok.M., and H. Rohracher. 2012. “Legitimizing Research, Technology and Innovation Policies for Transformative Change: Combining Insights from Innovation Systems and Multi-Level Perspective in a Comprehensive ‘failures’ Framework.” Research Policy 41 (6): 1037–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.10.015.

Further Reading on E-International Relations