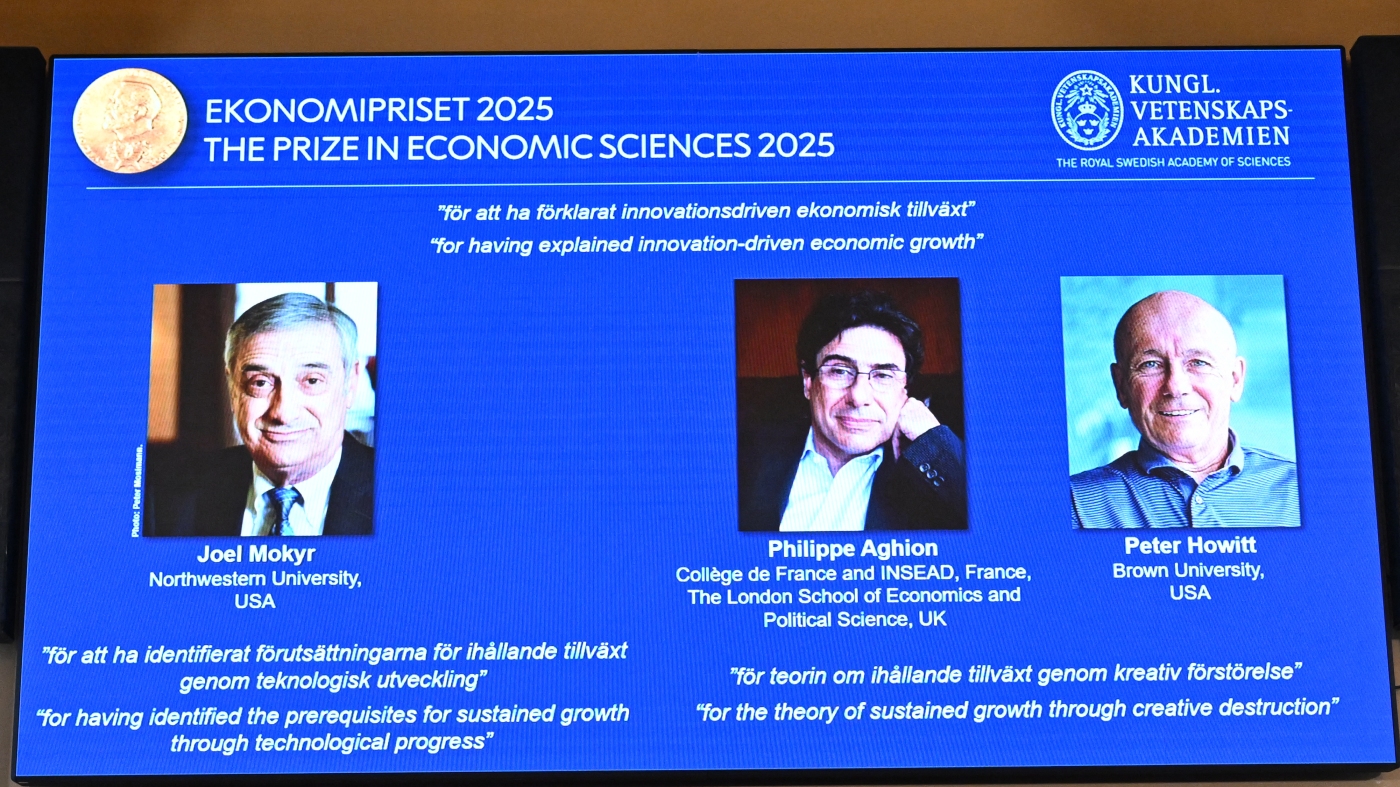

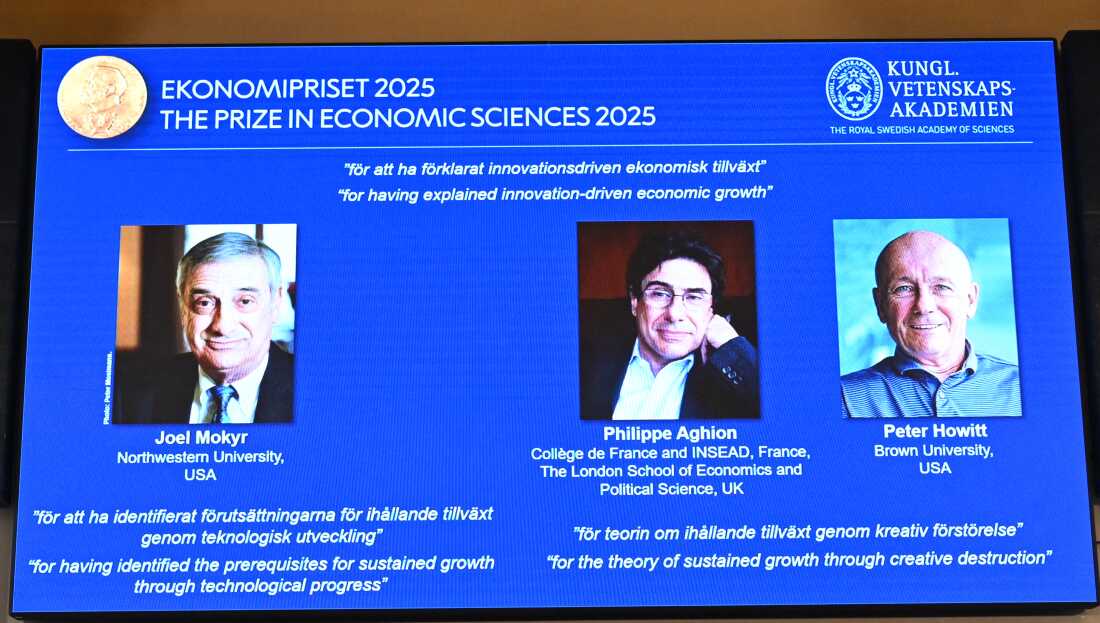

From left: A display exhibits images of American-Israeli Joel Mokyr, France’s Philippe Aghion and Canada’s Peter Howitt throughout the announcement of the 2025 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences on the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm on Monday.

Jonathan Nackstrand/AFP through Getty Images

disguise caption

toggle caption

Jonathan Nackstrand/AFP through Getty Images

If you graph the historical past of financial growth, it seems to be lots like a hockey stick laid on the bottom with its blade sticking up. That is, financial growth was fairly flat for millennia, after which, round 1800, it factors upward towards the sky.

It’s no secret that this inflection level — the place the stick’s deal with and blade meet — was the Industrial Revolution. That was a vital turning level within the historical past of humankind, when we left financial stagnation behind and commenced seeing monumental enhancements within the financial system and our lifestyle.

But why round 1800? Why did financial growth proceed propelling upward after that time? And why was Britain the primary society to expertise this revolutionary change?

The financial historian Joel Mokyr, a professor at Northwestern University and Tel Aviv University, was co-awarded the 2025 Nobel Prize in economics this week for his a long time of analysis making an attempt to reply these questions. (The economists Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt share the opposite half of the 2025 prize “for the theory of sustained growth through creative destruction.”)

For Mokyr, a vital motive why Britain turned the epicenter of the Industrial Revolution in 1800 has to do with science and technology. True, many societies earlier than Britain had seen scientific breakthroughs and technological progress. And generally, Mokyr finds, that led to some financial growth. However, no society noticed its financial system catapulted right into a form of sustained escape velocity away from stagnation earlier than.

Mokyr facilities his rationalization on why Britain was totally different by highlighting the way it embraced science, technology and disruptive change. He places a whole lot of emphasis on the function of the Enlightenment, or the mental awakening in science, philosophy, politics and different realms that swept Europe throughout and across the 18th century. It was a motion that revolutionized mental and political life and helped velocity up technological progress.

But that also would not clarify why it was particularly Britain that turned the epicenter of the Industrial Revolution. Other European nations, together with particularly France, additionally skilled the Enlightenment.

Mokyr’s analysis means that Britain was totally different as a result of, basically, the Brits operationalized the Enlightenment in the actual financial system greater than different nations. It wasn’t simply that scientists, philosophers and different thinkers had huge mental breakthroughs. In Britain, these scientific discoveries and a brand new mind-set filtered down to a talented class of mechanics and entrepreneurs and different “tweakers and tinkerers” who put new concepts to sensible use within the financial system. In this manner, “macro inventions” — or huge, paradigm-shifting scientific discoveries — fed a slew of sensible “micro inventions” that practitioners used to incrementally reshape the financial equipment of society, boosting productiveness and rocketing financial growth to the moon.

So, yeah, science and technology are tremendous essential for financial growth. But the essential ingredient, in accordance to Mokyr, was that there was additionally a talented inhabitants of staff and entrepreneurs who have been prepared and ready to put these advances into actual use within the financial system. Mokyr additionally emphasizes that British political establishments — specifically, its Parliament — have been extra open to the disruptive adjustments (or “creative destruction”) these new applied sciences unleashed, which regularly challenged the ability and prosperity of entrenched curiosity teams.

And right here is the place the opposite Nobel winners this 12 months, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, assist colour in additional of the image. They place inventive destruction on the heart of their common mathematical mannequin of financial growth.

Creative destruction is an concept that’s related to the late Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter. It refers to the wholesome course of of recent applied sciences, merchandise and companies changing outdated ones in a market financial system. This strategy of change entails older companies shrinking and even dying and, typically, staff dropping their jobs. So, yeah, there are losers within the course of, and, all through historical past, elites and curiosity teams have sought to block inventive destruction. But economists, together with Aghion and Howitt, theorize it is a essential course of for financial growth.

It’s lots to chew on because the globe grapples with the rise of a brand new wave of disruptive applied sciences, together with synthetic intelligence. But the Nobel winners’ work means that embracing this technological disruption — and discovering methods to operationalize these huge breakthroughs in the actual financial system — can be essential for the hockey stick’s blade to maintain pushing upward.

Anyways, we’re glad to say that Joel Mokyr has been a visitor on Planet Money earlier than. Check out our episodes: When Luddites attack and Imagining a world without oil. Mokyr additionally offered inspiration for a fictional audio drama we made as soon as, way back referred to as “The Last Job.”

And, if this history-of-ideas kind story is the form of studying you are into, could I encourage you to click here to preorder the Planet Money book. There’s a complete chapter on what causes financial progress and the function of technology, amongst different issues. It will get into extra depth than now we have house for right here. It has some enjoyable visuals, too. Planetmoneybook.com. Tell a good friend.