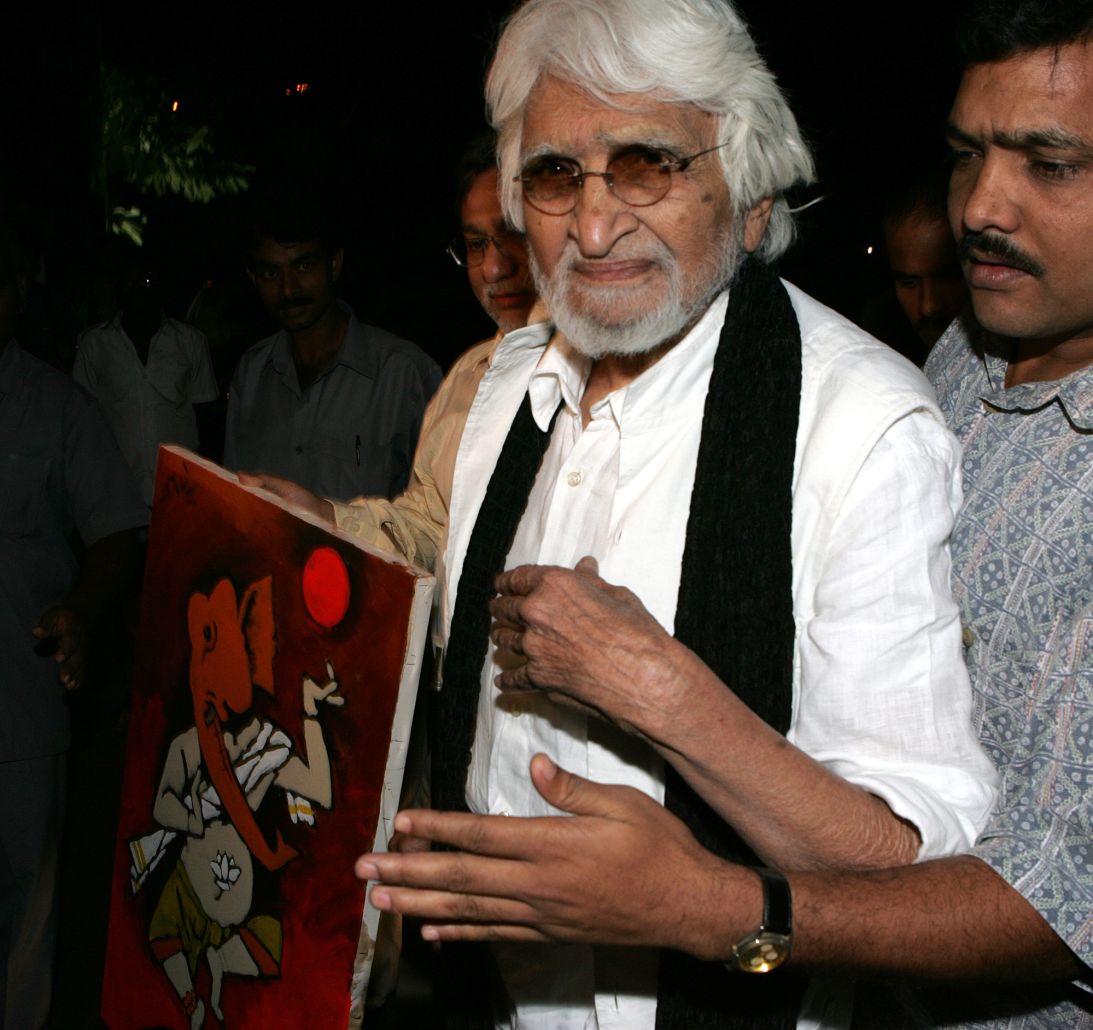

For the advanced legacy of M.F. Husain, considered one of Twentieth-century India’s most necessary artists, this 12 months has been a story of two auctions.

In March, considered one of the late painter’s monumental depictions of rural life, the 14-foot-long “Untitled (Gram Yatra),” grew to become the most expensive trendy Indian paintings ever to go beneath the hammer. The $13.75 million price ticket nearly doubled the earlier file, with onlookers at Christie’s in New York bursting into spontaneous applause.

Three months later, an auction of 25 long-lost Husain work in Mumbai was far much less celebratory. Police patrolled the premises and erected barricades at the auctioneer’s workplace after a right-wing Hindu nationalist group warned of “strong public agitation” if calls to cancel the sale — as a result of Husain’s “vulgar and obscene” portrayals of sacred figures — had been ignored.

The auction went forward with out incident. But the contrasting moods exemplified the painter’s standing as considered one of Indian artwork’s most celebrated however controversial names. As if to additional underscore his polarized status, this 12 months additionally noticed a Delhi court docket order the seizure of two “offensive” Husain work, whereas, earlier this month, the Qatar Foundation introduced plans for a complete museum devoted to his work (Qatar had given Husain citizenship after he fled India, in 2006, fearing for his security).

Known for daring, colourful explorations of folks and popular culture, Husain was lauded as a pioneer of Indian modernism and usually dubbed “India’s Picasso.” His work performed with icons in all their varieties, from Mother Teresa and Indira Gandhi to Bollywood stars and mythological figures from literary epics.

The artist’s portrayals of nude Hindu deities, nevertheless, stand accused of offending spiritual sentiments — a response his supporters consider is exacerbated by his Muslim heritage. As a end result, his later life was dogged by protests, authorized motion, loss of life threats and an arrest warrant. Despite later being exonerated by India’s supreme court docket, he died in self-imposed exile, in London, in 2011. In its assertion opposing June’s Mumbai auction, right-wing group Hindu Janajagruti Samiti mentioned that Husain “deliberately painted vulgar and obscene images of goddesses … thereby gravely hurting the sentiments of millions of Hindus in the world.”

The rekindling of previous grievances, nearly 15 years after his loss of life, could also be right down to burgeoning curiosity from the international artwork market. But reactions to Husain’s work are additionally a bellwether of Hindu nationalism, in response to Dr. Diva Gujral, an artwork historical past fellow at the University of Oxford’s Ruskin School of Art. While lots of his most contentious works had been produced in the Seventies, it is no coincidence that protests solely erupted in Nineteen Nineties, a decade when the Hindutva ideology flourished, communal tensions deepened and, Gujral mentioned, Muslims grew to become “a lightning rod” in India.

“The reception of Husain is such a good litmus test for Indian cultural politics, because there are times when it wasn’t controversial,” she added, calling the reactions a “way to take the temperature of the country.”

Icons previous and current

Hailing from an Indian department of the Sulaymani Bohras, a Muslim sect residing primarily in the Arabian Peninsula, Husain was uncovered to each Hindu and Islamic artwork from a younger age.

He was born in 1915 in Pandharpur, a pilgrimage city dotted with Hindu temples in western India. After his mom’s loss of life, he was despatched to review Urdu and Islamic calligraphy at his grandfather’s madrassa in Sidhpur, Gujarat. Husain later lived in the metropolis of Indore and immersed himself in folks traditions, like performances of the Hindu epic “Ramayana,” earlier than enrolling in artwork classes at the native artwork institute. In 1934, he bought his first portray on a roadside for 10 rupees.

His curiosity in iconography all the time stretched far past faith. In his early 20s, Husain moved to Mumbai to color billboards for the nascent Hindi movie business. It would show a formative expertise — one which formed his fascination with modern idols and Bollywood, in addition to his penchant for vivid colours and flattened, figurative varieties.

Then, in 1947, got here one other decisive second in the artist’s life: India’s independence from colonial rule and Britain’s partition of the subcontinent right into a Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan. Partly impressed by the spiritual strife that ensued, the painter co-founded the Bombay Progressive Artists’ Group (PAG), alongside main figures like F.N. Souza and S.H. Raza, later that 12 months.

The avant-garde group sought to forge a brand new visible language of — and for — India. Rejecting revivalist nationalism, its members fused native artwork traditions with outdoors influences, particularly these of European modernists like Pablo Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani and Henri Matisse (although Husain additionally traveled to China in the early Fifties), as they interrogated their nation’s rising identification.

“It was about creating something new, breaking with the past,” mentioned Gujra including that the group did greater than “simply take” from Western artwork. “They’re reinvigorating a language that’s made available to them through access to places like London and Paris. But it’s very much their own thing.”

For Husain, this meant a Cubist-inspired model rooted firmly in the Indian expertise. It is an strategy epitomized by the record-breaking “Untitled (Gram Yatra),” which he produced in 1954, although it went largely unseen for seven many years earlier than happening sale at Christie’s this 12 months. The narrative portray includes 13 vibrant vignettes, every containing a snippet of rural life. Abstracted villagers are depicted working the land, milling grain and tending to livestock. Elsewhere, a farmer symbolically reaches out of his portrait’s body to carry up a panorama in a neighboring vignette.

“It’s literally the farmer supporting the land, and supporting the state and the nation,” mentioned Nishad Avari, head of South Asian trendy and modern artwork at Christie’s. “This is Husain’s way of saying that, while we may be modernizing, post-independence, and entering this new era, it’s very important not to forget that the basis of the country is its rural folk.”

Despite the public consideration Husain’s later work attracted, his most precious work emerged throughout this early interval, Avari mentioned. “He’s playing this critical role of defining what it is to be an Indian artist in the new country of India, and what Indian modern art really means,” he added. “He’s a linchpin figure in defining this moment.”

As lots of Husain’s contemporaries moved abroad (together with Souza and Raza, who relocated to the UK and France, respectively), the painter remained in India, his everlasting muse. He nonetheless loved some international recognition, exhibiting in New York City in 1964 and taking part in the 1971 São Paulo Biennial in Brazil alongside Picasso. This interval additionally noticed Husain exploring feminine varieties, together with photos of Hindu goddesses like Durga and Lakshmi, generally in suggestive or erotic poses.

Husain maintained that he by no means supposed to degrade these deities. His topics weren’t the goddesses themselves, however their iconography — how they appeared in temple artwork, sculptures and friezes. Their nudity was drawn from Indian artwork historical past, not his creativeness, although the work had been nonetheless considered by some critics as a “kind of desacralizing act,” mentioned the University of Oxford’s Gujra.

“In Hindu nationalist politics, the bogeyman is the Muslim invader who outrages the modesty of the Hindu woman,” she mentioned. “For a lot of your average Indian viewers who didn’t have an enduring understanding of the nude and its art historical heritage… he becomes the Muslim disrobing the Hindu woman.”

“It reignited old ideas of the Muslim taking what isn’t his,” she added. “But the idea for Husain is that this heritage belongs to all of us.”

The whole Nineteen Eighties handed earlier than the work confronted important spiritual backlash. In that point, Husain was even welcomed into the political institution as a member of the Indian parliament’s higher home, the Rajya Sabha, the place he served till 1992.

But every little thing modified in the fall of 1996, when a Hindu month-to-month journal, Vichar Mimansa, revealed the artist’s nude depiction of the goddess Saraswati alongside an article headlined “M.F. Husain: A Painter or Butcher.” The incident led to a number of criminal complaints in opposition to Husain, who was then aged in his early 80s, starting a series of occasions that led to his self-imposed exile.

In 1998, Hindu fundamentalists attacked Husain’s Mumbai residence and galleries displaying his work. Eight years later, one other hardline group provided a 510-million-rupee (then $11.5 million) money reward for his homicide. The protests stretched past India’s borders, too, with London’s Asia House controversially canceling an exhibition of Husain’s work in 2006, citing safety issues, after Hindu teams demanded its closure and vandals defaced two of his work.

That 12 months, a court docket in Indore issued an arrest warrant for Husain. The offending picture, this time, was a newer portray that reimagined the map of India as a unadorned lady on her knees, metropolis names marking her physique. The artist publicly apologized for inflicting offense and denied giving it the identify “Bharat Mata” — or Mother India, a personification of the nation — claiming the work was untitled. This did little to appease his critics.

Concerned for his security and dealing with a whole bunch — or as he later suggested, 1000’s — of authorized circumstances, Husain left India in 2006. The Delhi High Court and, later, India’s Supreme Court finally rejected requires Husain’s summons and cleared him of obscenity fees, successfully quashing circumstances in different cities. In its ruling, in 2008, the Supreme Court criticized the emergence of a “new puritanism” in India, stating that erotic sculptures had been a standard sight in Hindu temples. Yet, Husain by no means felt it was secure to return to the nation once more.

His plight in the meantime grew to become a rallying cry for supporters of Indian secularism. Novelist Salman Rushdie was amongst these to criticize the Indian authorities for its “inadequate” safety of Husain and the freedom of expression he represented. “Violence and its ugly sisters, both Hindu and Islamic, have to be resisted,” Rushdie mentioned at an handle in Delhi in 2010. “They must be rebuffed. To appease it is the best way to ensure their growth. I am afraid India is going that way.”

Husain spent most of his closing years in Dubai, Doha and London. Upon surrendering his Indian passport to use for Qatari citizenship, he is reported to have mentioned: “India is my motherland, and I simply cannot leave that country. What I have surrendered is just a piece of paper.”

He additionally usually spoke of his want to return residence — together with to his good friend Abhishek Poddar, a outstanding collector and founding father of Bangalore’s Museum of Art & Photography, who recurrently mailed Husain his favourite Indore newspaper. “His love was India, and he always missed India,” mentioned Poddar. “I once said, ‘What is it that you miss? And he said, ‘What I really miss is the earth there. The mud.’”

Husain’s goddess work had been only a fraction of his life’s work. Even the most conservative estimates put his complete output at 30,000 to 40,000 artworks, spanning printmaking, writing and filmmaking of each the arthouse and Bollywood selection. He was equally prolific after leaving India: In 2007, he accomplished 51 work impressed by the Bollywood basic “Mughal-e-Azam,” and was, at the time of his loss of life, engaged on a collection of 99 artworks, reflecting the 99 names of Allah, telling the historical past of Arab civilization.

“He needed to paint all the time,” mentioned Poddar, who first met Husain as the artist waited for a elevate, with out sneakers, at a Kolkata bus cease in the early Nineteen Eighties. (The 57-year-old collector, then a teenage artwork fanatic, approached Husain after recognizing his flowing white beard from a weekly journal, and the pair struck up an unlikely friendship.) “I once saw him at his London property where he had between 25 and 30 works. I met him again two or three days later, and lo and behold, there were another 12 or 13.”

“There would have been at least a dozen occasions when he’s sitting with me and he’s drawing somebody’s portrait,” added Poddar, who holds a number of Husain works in his museum’s assortment.

Husain painted wherever and in every single place. Renowned as a showman, he even painted throughout dwell performances and instantly auctioned off the ensuing works. Taking commissions from Gulf royals and industrialist billionaires, he was one thing of an art-world movie star, his distinctive look, designer fits and status for strolling round shoeless all a part of his personal icon-building.

“He was known as the barefoot artist,” mentioned Avari, the Christie’s specialist. “He made {that a} factor. He would stroll round with this very lengthy paint brush, utilizing it as a cane. There was no mistaking the determine of Husain wherever he went.

“I don’t know anybody who doesn’t have a Husain story,” he added.

But if Husain was, to make use of Poddar’s phrases, a “brilliant marketing man,” is it believable that he had tried to use spiritual outrage to serve his personal ends? Gujra described the painter as a “contrarian” who “definitely liked controversy,” although she suggests he would neither have supposed nor anticipated the response his work provoked. “He was interested in mass images,” she defined.

Poddar in the meantime argued that his fiercely secular good friend handled Hindu icons the similar as all his different topics. In reality, Husain was additionally accused of blasphemy by Islamic teams over a tune in his 2004 film “Meenaxi: A Tale of Three Cities,” as its lyrics used phrases immediately from the Quran.

“If there were a pantheon of figures associated with Islam, I don’t think he would have looked at that any differently from the way he looked at Christianity, Sikhism, Hinduism or whatever else,” mentioned Poddar.

“I don’t think he ever had an anti-Hindu agenda,” he added. “Ever.”