Affordable, versatile, extremely robust and domestically obtainable, concrete is the world’s most used manmade material.

But it additionally has an enormous carbon footprint, accounting for around 8% of world greenhouse emissions.

The concrete and cement sector has been making an attempt to scale back its environmental impression for years by way of sustainable concrete mixtures or environment friendly designs.

Now, a analysis crew on the University of Pennsylvania has mixed each novel supplies and a material-saving design, with out compromising on energy and sturdiness.

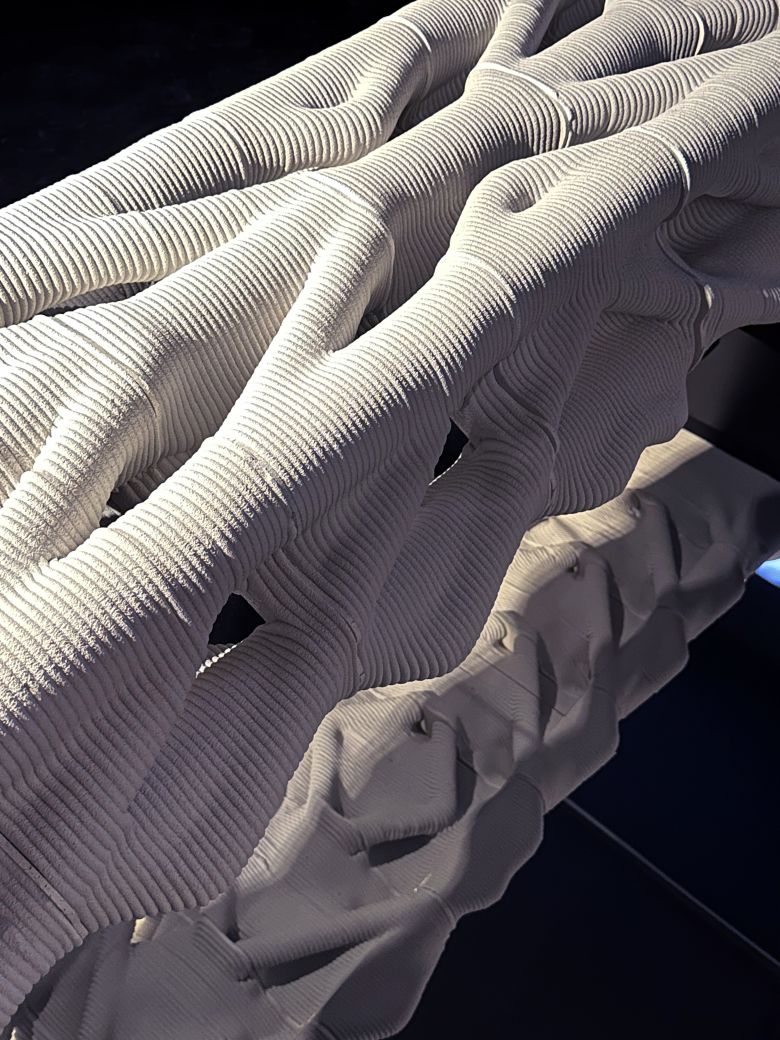

The project, known as Diamanti, takes inspiration from nature and makes use of a robotic 3D printer to create complicated, lattice-like patterns with a sustainable concrete combination.

While most common concrete absorbs carbon dioxide (as much as 30% of its manufacturing emissions over its whole life cycle, based on some analysis), Diamanti’s enhanced concrete combination absorbs 142% more carbon dioxide than standard concrete mixes.

Its first design, a pedestrian bridge, makes use of 60% much less materials whereas retaining mechanical energy, says Masoud Akbarzadeh, an affiliate professor of structure on the University of Pennsylvania and director of the lab that spearheaded the challenge.

“Through millions of years of evolution, nature has learned that you don’t need material everywhere,” says Akbarzadeh. “If you take a cross section of a bone, you realize that bone is quite porous, but there are certain patterns within which the load (or weight) is transferred.”

By mimicking the buildings in sure porous bones — referred to as triply periodic minimal floor (TPMS) buildings — Diamanti additionally elevated the floor space of the bridge, growing the concrete combination’s carbon absorption potential by one other 30%.

“The surface area, together with this material property, maximizes the reaction with carbon at the microscopic level,” says Akbarzadeh. “That contributes a lot to both (carbon dioxide) reduction and absorption.”

The challenge, launched in 2022 in collaboration with Swiss-headquartered chemical firm Sika and with grants from the US Department of Energy, is now gearing as much as construct its first full-size prototype in France.

Concrete’s energy, sturdiness and security, like fireplace resistance, “are fundamental to why it is used at the scale that it is globally,” says Andrew Minson, director of concrete and sustainable development on the Global Cement and Concrete Association.

The cement trade has made vital efforts to enhance sustainability, decreasing its carbon emissions by 25% per metric ton between 1990 and 2023. However, the sector’s emissions are increased right now than in 2015 as a result of elevated demand, based on the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Most of its emissions — round 90% — come from cement, says Du Hongjian, a senior civil engineering lecturer on the National University of Singapore, who shouldn’t be concerned with the Diamanti challenge.

Cement is a binding agent that hardens when blended with water, and is utilized in development supplies, together with concrete, the place it holds collectively aggregates like sand and stone.

The energy-intensive course of to make cement entails breaking down limestone at temperatures as much as 2,000 degrees Celsius (3,632 Fahrenheit) in a kiln, which generates carbon emissions. Additionally, limestone is a calcium carbonate that releases carbon dioxide at excessive temperatures, accounting for the majority of cement emissions, says Hongjian.

Switching out some cement for different supplies will help scale back its carbon footprint, and several other corporations and organizations are exploring extra absorbent concrete mixes: Japan’s CO2-SUICOM states its concrete combine is carbon damaging, and UK-based Seratech is one in every of a number of corporations incorporating the CO2-absorbing mineral olivine into cement to make it extra sustainable.

Diamanti’s concrete combination, developed by Dr. Shu Yang on the University of Pennsylvania’s Material Science Department, makes use of diatomaceous earth (DE), a naturally porous, silica-rich materials made out of fossilized algae, to interchange a number of the cement.

This biomineral creates “channels” within the concrete that enable carbon dioxide to penetrate under the floor, says Hongjian. However, DE had a world manufacturing of two.6 million tons in 2023 — so whereas Hongjian believes the fabric has potential, “the supply chain must be considered for future wider adoption” whether it is to satisfy the massive calls for for concrete, he says.

Minson agrees that provide could possibly be a problem, however that the place the uncooked materials is offered, it may present a “niche solution.”

“There’s no silver bullet. We need to be doing all the different actions that we can to manage material demands and reduce carbon,” Minson provides.

Another innovative facet of the analysis is the elevated floor space: concrete absorbs carbon dioxide, however “only the surface concrete, which is exposed to the air, has this access to CO2,” says Hongjian.

Diamanti’s innovative two-pronged method gives the sector with options that could possibly be used collectively, or individually, says Hongjian, including: “Even without the material innovation, the higher surface itself allows higher CO2 absorption.”

Before utilizing Diamanti in the actual world, the crew needed to take a look at it, by making a bridge prototype.

The bridge is modular, and every block printed by utilizing a robotic arm after which linked with a tensile cable. According to Akbarzadeh, 3D printing reduces development time, materials, and power use by 25%, and its structural system reduces the necessity for metal by 80%, minimizing use of one other emissions-heavy materials. He added that utilizing the approach with Diamanti’s concrete considerably cuts greenhouse gasoline emissions in comparison with common development strategies, and reduces development prices by 25% to 30%.

First, the crew constructed a five-meter-long prototype to reveal feasibility, earlier than establishing a bigger 10-meter model with materials supplied by Sika Group Switzerland for load testing, which it handed with flying colours, says Akbarzadeh: “It exceeded all our expectations.” The prototype is presently on show on the European Cultural Center in Venice for the Venice 2025 Architecture Biennial.

Akbarzadeh and the crew published their findings in Wiley’s Advanced Functional Materials journal earlier this yr, and had initially hoped to construct the challenge’s first full-scale bridge in Venice.

But, after the town modified its laws concerning new large-scale buildings, the crew began on the lookout for different iconic waterways in Europe. Akbarzadeh partnered with digital design studio Fortes Vision to create conceptual digital renderings that visualize the bridge over the River Seine within the middle of Paris.

In September, the challenge secured approval to assemble its first bridge in France, though the situation continues to be being determined. Akbarzadeh is happy to check their designs in the actual world, the place they may proceed to carefully monitor and consider the construction.

Beyond bridges, the crew can be exploring different architectural functions, akin to prefabricated flooring methods. It’s not a one-stop answer, says Akbarzadeh, however he hopes that Diamanti can create “a whole new world of possibilities” for concrete.