NCS

—

In the previous picture studios of Lagos, Nigeria, negatives had been being burned. No longer wanted or needed, they had been too tough to retailer, the topics had moved on or died, and the picture labs that printed them had lengthy since shuttered.

Those that weren’t discarded or set alight had been left to degrade in rice baggage and cardboard containers, the humid Lagos air slowly destroying the emulsion.

When Karl Ohiri, a British Nigerian artist, first heard about this, he was shocked.

“I was witnessing this history that was on the verge of being destroyed,” he informed NCS.

These analog photographers captured life in Lagos from the Nineteen Sixties to the early 2000s.

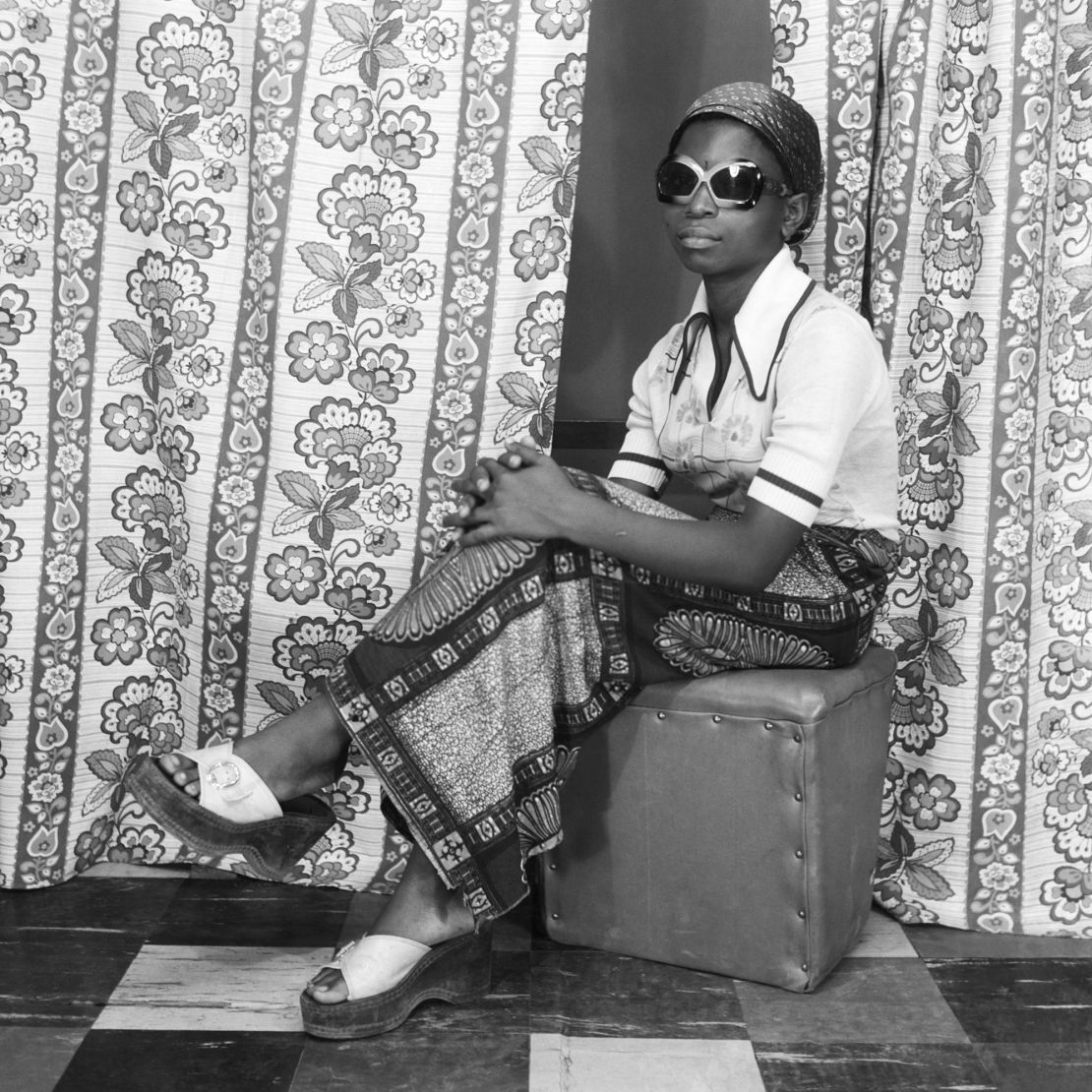

From black and white portraits of younger males of their bell bottoms, to a lady praying in entrance of a backdrop of the Islamic holy metropolis of Mecca, to shade photos of individuals displaying off their new cassette gamers, the photographs these photographers made had been a glimpse into Nigeria’s largest metropolis earlier than the appearance of digital pictures.

However, they’d by no means been digitized or archived — there have been no backups.

In nations just like the UK, Ohiri mentioned, museums might need taken the photos, including them to their huge archives; London’s V&A Museum has 800,000 photos in its assortment and the National Portrait Gallery has 250,000.

But in Lagos, Ohiri defined, “there wasn’t anywhere to house them.”

Ohiri and his associate Riikka Kassinen launched Lagos Studio Archives to save the collections. They have spent the final 9 years looking down studios and photographers, cataloguing their archives, and creating exhibitions of the work.

It has not at all times been straightforward. “Lagos moves fast,” Kassinen defined; many of the photographers have since died, their studios torn down and new developments constructed of their place. There is usually so little hint of the studios that “it’s almost like (they) never happened,” mentioned Ohiri.

Even if the pair may discover the photographers, generally they had been too late. “We’ve gotten to some photographers who had three or four decades of work that doesn’t exist anymore,” Ohiri mentioned. “All of that history and heritage and there’s nothing left… it takes all of that time to amass, and just half a second to put some kerosene on it and light it up and that’s it. Just gone.”

Initially, many of the photographers didn’t perceive their curiosity. “They just thought we were crazy,” Ohiri mentioned. Now they’ve the work of no less than 25 photographers within the archive, although they can’t be certain of an actual quantity as some of the troves they got contained a number of photographers’ work.

Nor do they know what number of negatives are within the assortment, solely that it’s within the a whole lot of hundreds, piling up in Ohiri and Kassinen’s studio in Helsinki, Finland. “We might not be able to (digitize) everything in our lifetimes,” Ohiri conceded.

The ’70s was a interval of fast change in Nigeria. The nation’s civil battle had ended, Nigerian oil had boomed, and an more and more city inhabitants was enraptured by Fela Kuti’s Afrobeat. Photo studios grew to become a spot for individuals to doc their on a regular basis lives, showcase their accomplishments and have a good time occasions. “It was a theater of dreams where people could really show their aspirations,” Ohiri mentioned.

In the midst of these social and cultural adjustments sweeping by Lagos was Abi Morocco Photos.

Made up of husband-and-wife photographers John, who died in 2024, and Funmilayo Abe, Abi Morocco Photos labored from the early Seventies to 2006. First from a studio on Aina Street, and later shifting, the pair took portraits on the studio, in addition to visiting clients’ properties, attending occasions and ceremonies, and capturing portraits within the streets.

Ohiri and Kassinen lately curated an exhibition of the Abes’ work from the Seventies on the Autograph gallery in London, and have plans for a photobook of the couple’s work.

The present adopted the archive’s inclusion within the New Photography Exhibition at New York’s MoMA, in 2023. “Archive of Becoming” was an experimental sequence of pictures, culled from broken negatives. Ohiri and Kassinen had to put on masks to defend them from the fumes and mould that had grown on the discarded negatives as they painstakingly preserved them.

Now the archive is planning a venture on feminine photographers and so they need to make the general assortment accessible to residents of the megacity by books and exhibitions.

Despite exhibiting the work world wide, the pair have by no means met any of the paying purchasers — the closest they’ve gotten is a good friend who acknowledged their uncle in a single of the photographs. They hope that individuals would possibly someday acknowledge the scratched black and white portraits, the mold-stained faces, and time-faded colours, in order that the hundreds of negatives can turn into not only a doc of town, however “a family archive of Lagos.”