Last fall, Yoncha, a Metropolitan State University of Denver affiliate professor of Art, introduced 17 superior portray students with canvases that have been seasoned with literal grime. And, “dirt seasoning” — a visible illustration of microbes lively on the carcass web site.

The canvases had spent 49 days buried in Genessee Park 5, 10 or 15 meters from a bison carcass. The aim, stated Sarah Schliemann, Ph.D., assistant professor of Environmental Science, was to “see what happens to the soil” because the deceased bovine decomposed.

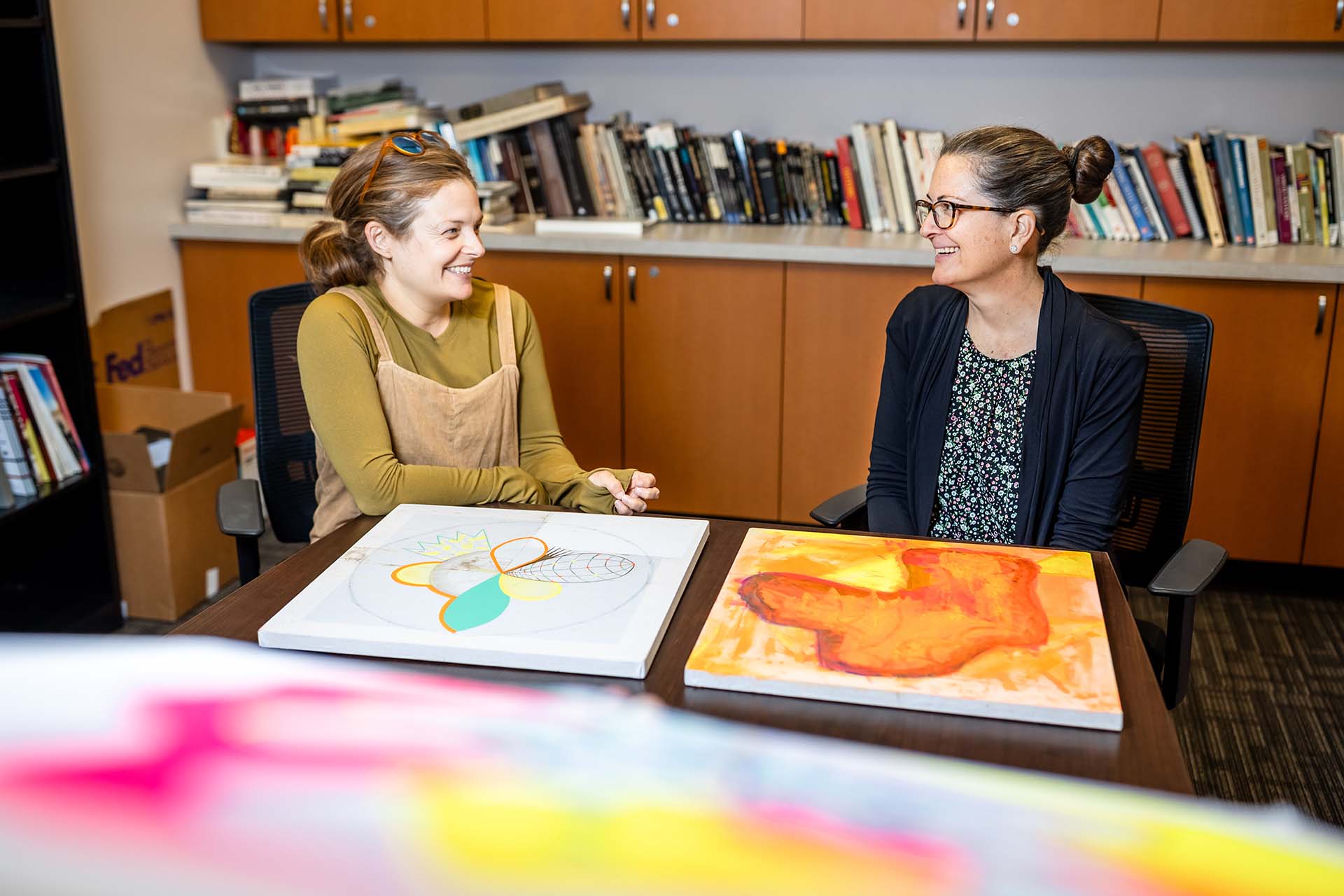

Studying soil, and the way animals and atmosphere have an effect on it — and vice versa — is what Schliemann does. Art is what Yoncha does.

Their undertaking united science and artwork.

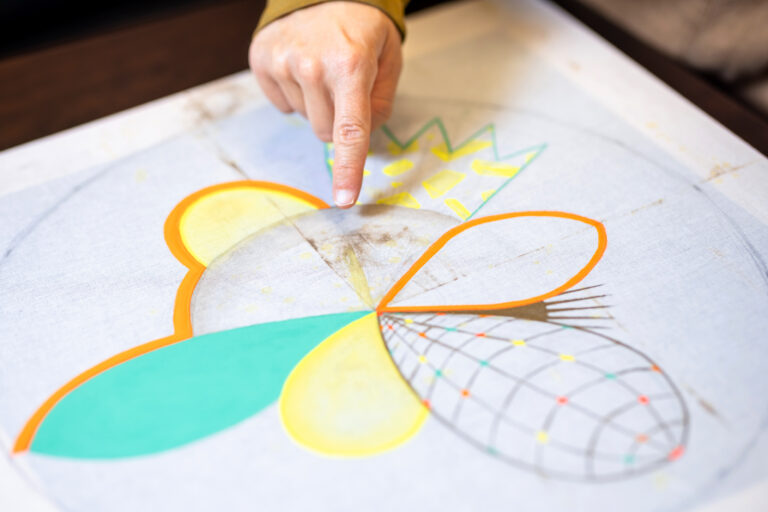

MSU Denver professor Anne Yoncha factors to the grime on one of many pupil artwork items. Photo by Alyson McClaranWhile Yoncha handed out the dirty canvasses to students, Schliemann was analyzing soil samples from the world the place the canvasses had been buried, to study the concentrations of components reminiscent of potassium, sodium, magnesium. She wished to doc how proximity to the decaying animal affected the presence of these components. Not surprisingly, the soil closest to the animal’s stays contained the best quantities of the vitamins. It’s all a part of Schliemann’s work on a better effort to know not solely how the atmosphere impacts bison, but in addition how bison affect the atmosphere.

Once the information was plotted, Schliemann turned it over to Yoncha, whose students crammed the canvasses with their interpretations of that information and of the weather.

“This one’s boron I think,” Yoncha stated, one of many summary works her students had produced.

“The art project lets us explore data in a very sensory way,” Yoncha stated. It’s an opportunity to discover “How do we encode visually what these chemicals do?”

Now, Yoncha is creating an animation from the artwork, which can be accompanied by music.

RELATED: Dreams come true for students in the environmental sciences

Meanwhile, over within the Music Department, students additionally had the chance to remodel Schliemann’s grime into artwork — on this case, music.

“The idea is when we change data into different formats, we get a better understanding of that data,” stated David Farrell, DM, affiliate professor of Music.

“The music class is working with the same soil data,” Schliemann stated. “I gave them my data, which is basically a table of numbers that reflect the chemical makeup of the soil.”

Turning that form of information into music, or sound, is an rising area known as sonification of information, and it’s one, Farrell stated, that “fits a lot of the things I’m interested in,” together with computerized music and numbers.

In the primary few weeks of sophistication, students familiarized themselves with the sonification of information area, after which with the instruments they wanted to transform information factors to music.

The three school members hope to share the artwork and musical creations with the general public via collaboration with the chamber music group The Playground Ensemble. Ultimately, they’d wish to showcase each on the Denver Museum of Nature & Science.

Beyond merely being a novel strategy to creative expression, Farrell sees loads of office potential in sonification of information. “A lot of careers involve processing and interpreting numbers,” Farrell stated. “If you’re a data person who wants people to understand your data, whether in business or education, or whatever else, this is a tool we can use to share or process our data and make it understandable.”

Learn extra about Environmental Science at MSU Denver.