NCS

—

Photographer Derek Ridgers’ introduction to the Cannes Film Festival arrived in 1984, when he was commissioned to shoot the DJ and rapper Afrika Bambaataa — on the town to advertise his cameo in Stan Lathan’s “Beat Street” — for the music journal, NME. “I don’t think I’d ever really thought about Cannes, or the film festival, before I went,” Ridgers, broadly celebrated for his distinctive portraits of British subcultures, informed NCS by way of e mail. “Every year one sees items about it on TV, but it hadn’t impacted my life in any significant way.”

Ridgers would return to the French resort city an additional 11 occasions, throughout which he stated he “only ever saw two films” — “Beat Street” and Thaddeus O’Sullivan’s “December Bride” (he’d been at artwork faculty with the director). “If you’re on the French Riviera and the sun’s out, why would you choose to go to the cinema if you didn’t have to?” he reasoned. Instead, Ridgers targeted on the compelling and typically controversial scenes that unfolded round him, capturing celebrities, younger fashions and upcoming actresses, in addition to fellow photographers.

Three many years on, some 80 images from Ridgers’ archive have been introduced collectively in a brand new e-book, “Cannes,” printed by IDEA. The pageant it presents is in some ways a special variety of spectacle to its modern iteration. This yr’s version, which runs via May 24, will largely be skilled by way of social media (the official Festival de Cannes Instagram web page has 1.3 million followers alone, whereas 1000’s of tagged movies populate TikTok). In Ridgers’ photos, made within the Nineteen Eighties and Nineties, there’s not a single cellphone and barely a degree and shoot camera; star-making-moments, political statements and style historical past had been all sometimes reported by TV and printed media.

“My interest has always been people and, I suppose, a study of the human condition,” stated Ridgers, who, alongside his skilled assignments, spent a lot of the Nineteen Eighties and the last decade prior documenting London’s punks, skinheads and New Romantics. “The film festival was my first extended foray into reportage, but it’s still all people doing what people do,” he famous, reflecting on how his e-book “Cannes” was formed by this similar curiosity, in tandem together with his rejection of the extra conventional crimson carpet set-up.

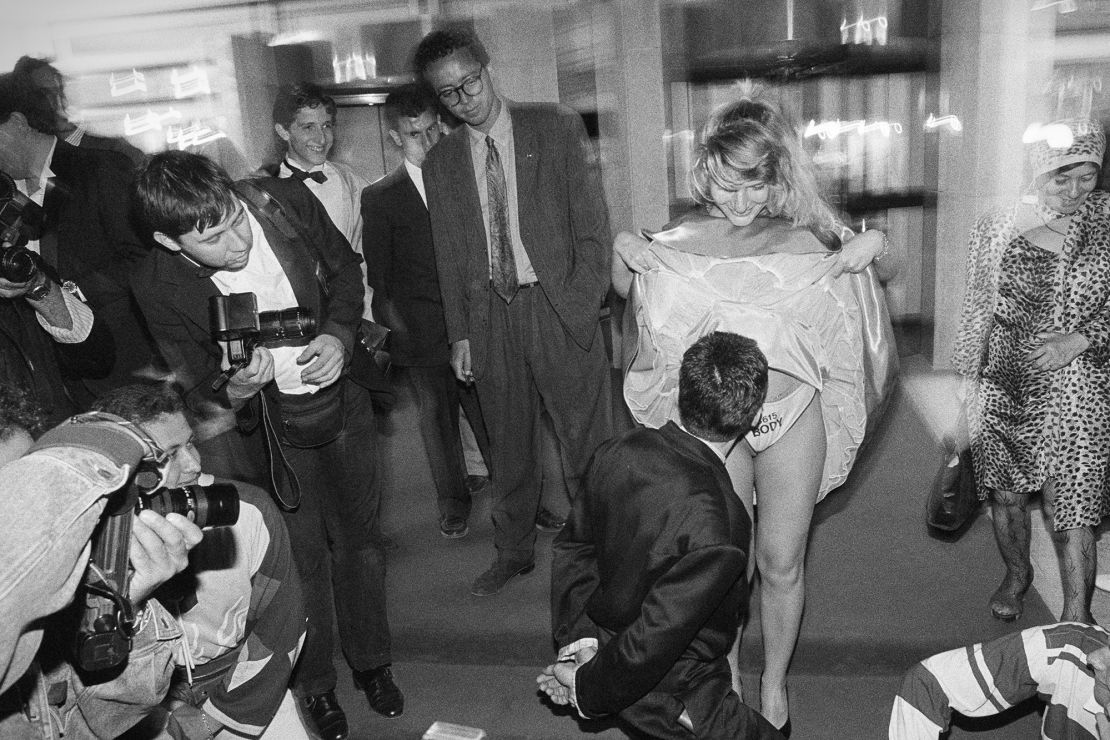

“There’s so much of life’s rich pageant on show during Cannes, there are great photographic opportunities almost everywhere,” he continued. Shooting each in shade and black and white, Ridgers captured icons resembling Clint Eastwood, Helmut Newton and John Waters, in addition to then-up and coming fashions like Frankie Rayder, who seems on the e-book’s cowl wearing diamonds and fur (the encircling crowd adopting informal denims and T-shirts), and performers attending the Hot D’Or grownup movie business awards too, together with the late Lolo Ferrari.

“During the years I was going, the film festival seemed to become a bigger and bigger deal,” shared Ridgers. “When the porn stars were having their awards show there as well (the Hot D’Or’s ran from 1992-2001), that added a layer of craziness and made for some interesting photographic juxtapositions. The main film festival seemed to take itself awfully serious, and having the porn stars there lightened the mood somewhat.”

Young ladies then, grownup entertainers and wannabe movie stars alike, are a relentless all through the brand new e-book, posing with buddies or performing for the camera; displaying off in an try and emulate Brigitte Bardot’s culture-shifting debut on the pageant in 1953, whereas selling “Manina, the Girl in the Bikini.” Ridgers, adopting the gaze of a bystander, recorded all of it, from the playful to the outrageous, and typically the outright questionable, as within the image of one other photographer taking an upskirting shot. “It seemed shocking then, too, which was why I took the photograph,” he defined. “I was appalled by the unabashed brazenness of it. Someone doing that nowadays would, rightly, get arrested.”

Stressing that he by no means thought of himself above his friends, Ridgers additional recalled that he additionally by no means felt any sense of kinship with them, and the e-book concludes with a picture of some photographers holding and discussing one of his images, oblivious to his presence. “The whole time I went to the festival, I don’t think I had one conversation with any of the other photographers,” he stated. “They shouted at me occasionally, for getting in their way, but that’s hardly a conversation. It sounds terrible, I know, but I just ignored them. I’m competitive and very focused — if I’m standing around chatting, I may be missing a good photograph.”

In “Cannes” nonetheless, the temper is one of debauchery with a light-hearted sensibility. “I’m serious about my work but this is not a particularly serious photobook,” stated Ridgers, acknowledging the character of its contents. “Most of the photographs are frivolous, and some are simply outrageous. These days, because of the French law of droit à l’image (a right to one’s image) it’s harder to publish photographs of people in public without their permission — how that works in the era of the camera phone, I have no idea. My photographs are testament to what fun, crazy and at times, ludicrous, things happened back then.”